The comet nucleus has a diameter of almost 130 kilometers, making this sample as much as 50 times larger than the heart of most known comets.

Almost a year ago, astronomers stumbled upon a special object by accident. A comet suddenly appeared in photos of the night sky. And what kind. Investigators soon suspected that it was a large specimen. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have now got an even closer look at the massive comet. And it turns out that comet C/2014 UN271 is even the largest ever discovered.

Size

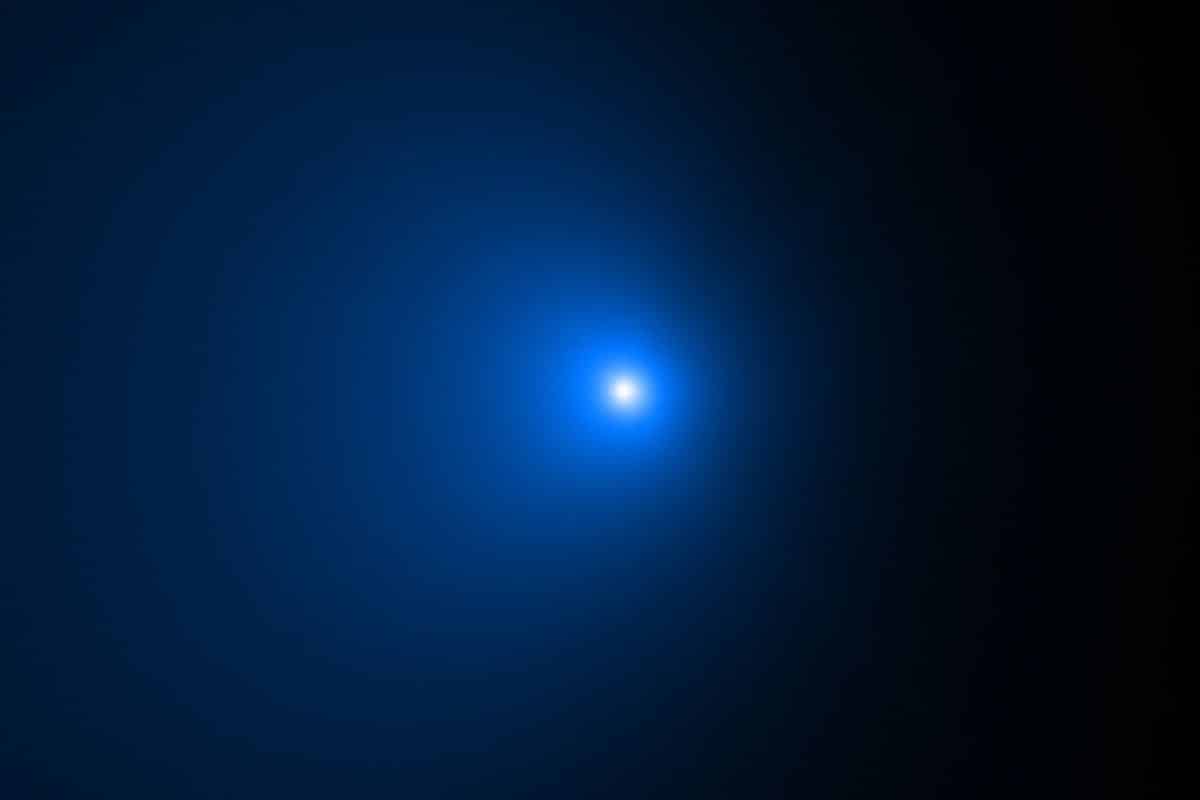

Using the Hubble Space Telescope, researchers are in a new study succeeded in distinguishing the solid comet nucleus (i.e. the solid part of a comet, which largely consists of particulate matter, rocks and frozen gases) from the enormous dusty shell around it. A big challenge, since the comet is a great distance from the sun. However, Hubble detected a bright peak of light at the precise spot of the core. The researchers then fabricated a computer model of the surrounding coma. Then this glow of the coma was subtracted from the whole, leaving the core. This then allowed the team to determine the size of the core.

(1) Comet C/2014 UN271 seen through the eyes of Hubble (2) a model of the coma (3) the remaining nucleus of C/2014 UN271. Image: NASA, ESA, Man-To Hui (Macau University of Science and Technology), David Jewitt (UCLA)

IMAGE PROCESSING: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

The calculations show that the comet nucleus has a diameter of almost 130 kilometers. This makes this comet nucleus no less than 50 times larger than the heart of most known comets and more than a third larger than the previous record holder – a comet with a diameter of ‘only’ 96 kilometers. The mass of C/2014 UN271 is estimated to be an impressive 500 trillion tons; hundreds of thousands of times more massive than the mass of an average comet.

Comets, the inhabitants of deep space, are among the oldest objects in our solar system. These icy celestial bodies are remnants of the early days of our solar system, when planets were forming. We currently know 3775 comets in our solar system. They are made up of ice, dust and small rocky particles and can sometimes have very crazy orbits around the sun. Comets often have a tail. When the ice ball comes close to the sun or another star, it heats up. The ice in the comet sublimes (evaporates) and rushes away from the surface. In doing so, it carries light dust and debris particles with it. This creates a dust tail and coma (dusty atmosphere) so characteristic of comets. Then the comets return to distant corners of our solar system.

At the moment, the giant comet is hurtling through our solar system at a whopping 35,000 kilometers per hour, towards the sun. However, according to the researchers, you don’t have to worry; C/2014 UN271 will keep a safe distance and not even get past planet Saturn. The comet is currently about 3.2 billion kilometers from our parent star. At that distance, the temperature is around -210 degrees Celsius. Incidentally, this is hot enough for carbon monoxide to sublimate off the surface and cause a dusty coma.

Amazed

Astronomers are stunned by the discovery. “This is an amazing object,” said researcher Man-to Hui. “Especially given how active the comet is while it is still so far from the sun.” According to researcher David Jewitt, this comet is just the tip of the iceberg of the many thousands of comets that are too faint to see in the outer reaches of our solar system. “We have always suspected that C/2014 UN271 must be large because it is so bright at such a great distance,” he says. “Now we confirm that this is indeed the case.” In addition, the new Hubble measurements convincingly suggest that C/2014 UN271 has a darker core surface than previously thought. “It’s blacker than coal,” Jewitt said.

The comet has been falling toward the Sun for more than 1 million years, the researchers say. In a few million years, the comet will return to its still somewhat mysterious home port: the Oort cloud.

Source material:

†Hubble confirms largest comet nucleus ever seen” – Hubble

Image at the top of this article: NASA, ESA, Man-To Hui (Macau University of Science and Technology), David Jewitt (UCLA) IMAGE PROCESSING: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)