Will the Rosalind Franklin rover ever see Mars? It has been a real question – since the war in Ukraine.

After years of designing and tinkering, the very first European Mars rover is officially finished. ESA announced this in a short press statement; the robber has the System Qualification and Flight Acceptance Review that took place this month passed with flying colours.

called off

It means the rover could have been shipped to the Baykonur cosmodrome in time for launch and – as planned – actually launched there sometime after September 20. But it’s not going to happen. Instead, the rover is currently being prepared for storage in Italy. And no one knows when Rosalind Franklin will leave storage again.

War

A few months ago, such a scenario would have been unthinkable. But the war in Ukraine has changed everything. ESA has ended cooperation with Russia, which has far-reaching consequences for the ExoMars mission of which Rosalind Franklin is part and for which ESA worked closely with the Russian space agency Roscosmos. For example, although ESA now has a brand new Mars rover, there is no way to transport it to Mars and have it landed there. For those two parts of the mission, ESA is completely dependent on Roscosmos, which would provide both the launch vehicle (a Proton-M) and the Marslander (named Kazachok).

A few weeks ago, ESA announced that it saw no other option than to postpone the launch of the Rosalind Franklin rover. Nevertheless, it was determined this month – as planned – whether the rover had been ready for launch. And so ESA must now conclude – no doubt with mixed feelings – that that had been the case. In the absence of a launcher and lander, however, Rosalind Franklin remains transfixed for now.

Earlier postponement

This isn’t the first time the ExoMars rover has faced adversity. Previously, problems with the landing parachutes meant that the launch – originally planned for 2018 – was delayed by two years. In 2020, among other things, the pandemic meant that the launch had to be postponed again by two years. And now September 2022 is also not feasible due to the war in Ukraine.

Alternatives

How to proceed remains to be seen. ESA is currently frantically searching for alternatives. For example, it is being explored whether ESA – possibly in collaboration with space companies or other space organizations – is able to send the rover to Mars. That investigation is expected to take several months, after which ESA member states will have to comment on any resulting proposals. A launch in 2022 is therefore no longer possible. It means that the launch automatically moves to 2024 (see box) or later.

“I hope our member states will decide that this is not the end of ExoMars, but a rebirth of the mission, perhaps even a trigger to develop more European autonomy,” said David Parker, on behalf of ESA. “We are counting on reshaping the mission with the help of international partners and brilliant teams and European expertise (…) and we are focusing on the steps to be taken to bring this amazing rover to Mars and do the work there. let it do what it was designed for.”

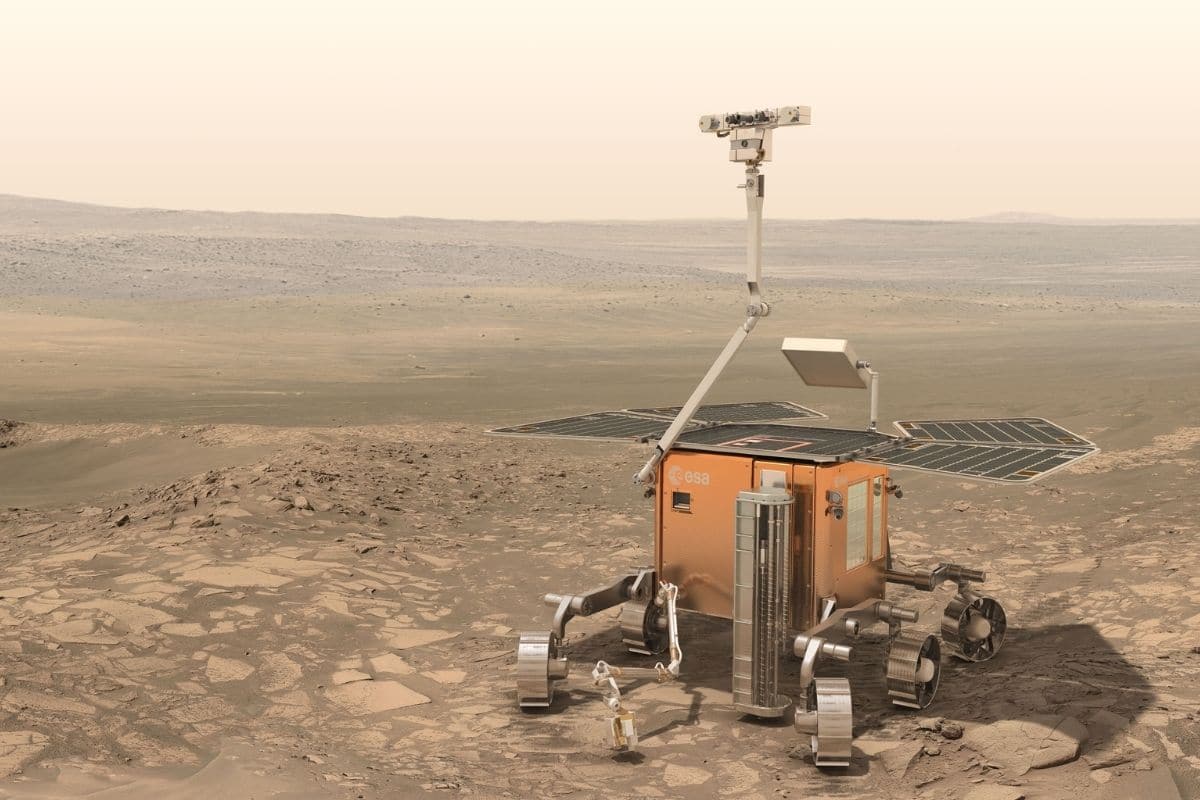

Rosalind Franklin is the very first Mars rover built by ESA. The rover is part of the ExoMars program that has two missions. The first mission consists of a Mars orbiter that was successfully launched in 2016 and is still orbiting Mars. This orbiter conducts research on trace gases (gases that make up less than 1 percent of the Martian atmosphere) with a focus on methane: a gas that can be generated by both biological and non-biological processes. The second mission consists of the rover Rosalind Franklin and lander Kazachok. Together, the ExoMars missions must reveal whether there is or has been life on Mars. Rosalind Franklin is equipped with a drill that can drill up to 2 meters deep. “DNA molecules and viruses are probably too fragile to survive in the ground for four billion years,” said study researcher Jorge Vago. “But we hope that our rover (…) will allow us to study organic molecules at some depth and perhaps find some evocative traces of decayed life.”

Source material:

†Rover ready – next steps for ExoMars” – ESA

Image at the top of this article: ESA / AOES Medialab