Painful long-term gut conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), affect women more often than men. A new study in mice suggests a biological reason for this difference and points to possible new treatments.

Women of reproductive age are especially likely to report gut problems like IBS. Many say their pain is brushed off by doctors, often blamed on stress, diet, or “just hormones.” This research suggests the pain is real and driven by specific biological processes.

The study, published December 18 in Science, describes a complex chain of events involving estrogen, gut cells, bacteria, and chemical messengers. Although the work was done in mice, it offers strong clues about what may be happening in people.

What is gut (visceral) pain?

Gut pain is known as visceral pain, meaning pain that comes from internal organs. Nerves in the abdomen and torso carry these pain signals to the brain. This pain can feel like bloating, sharp cramps, or a constant dull ache. About 10 percent of people worldwide have IBS, and most of them are women. IBS may involve diarrhea, constipation, or both.

Researchers have long known that estrogen, a major female sex hormone, affects gut pain. Estrogen levels change during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, and many women notice that their IBS symptoms change during these times.

In earlier research, scientists found that female mice were more sensitive to gut pain than male mice. When estrogen was removed, that extra sensitivity disappeared. This showed that estrogen plays a key role in making gut nerves more sensitive to pain.

How hormones send signals in the gut

For a hormone like estrogen to affect a cell, that cell must have a matching receptor. A receptor is a protein on or inside a cell that recognizes a specific chemical and triggers a response.

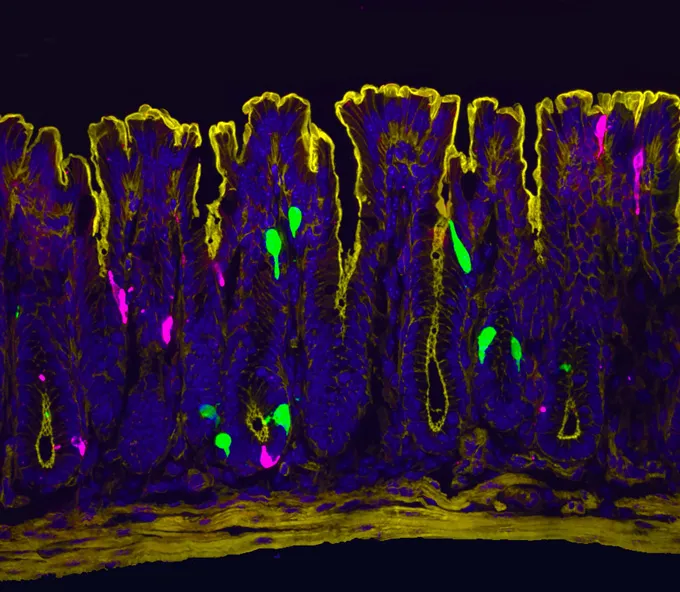

The researchers first thought estrogen receptors would be found on cells called enterochromaffin cells. These are rare cells in the gut that produce about 90 percent of the body’s serotonin. Serotonin is a chemical messenger best known for its role in mood, but in the gut it helps control movement and pain. When serotonin is released, nearby nerve cells pick up the signal and send pain messages to the brain.

Surprisingly, the scientists could not find estrogen receptors on these serotonin-producing cells.

A multi-step “telephone game” between cells

Instead, the researchers discovered that estrogen affects gut pain through a multi-step process involving several different cell types — similar to a game of telephone, where a message is passed along through intermediaries.

They found estrogen receptors on another rare gut cell called an L cell. When estrogen binds to L cells in the colon, these cells begin producing a new receptor called OLFR78 and place it on their surface.

This receptor detects short-chain fatty acids, which are small molecules made by gut bacteria when they break down certain sugars in food. (These sugars are commonly found in foods high in FODMAPs, a group of carbohydrates known to trigger IBS symptoms in some people.)

When L cells sense these fatty acids, they release a hormone called peptide YY (PYY). PYY normally helps regulate digestion and appetite. In this case, it acts as a messenger.

Using lab-grown mini-gut models called organoids, the researchers showed that PYY travels to the enterochromaffin cells. Those cells then release a burst of serotonin. This serotonin activates nearby nerves, which send pain signals to the brain.

Why this matters for treatment

Most current treatments for IBS focus on serotonin, trying to block or reduce its effects. This study suggests there are more points in the pathway that could be targeted. Future treatments might aim at estrogen receptors in the gut, the OLFR78 receptor, or PYY itself.

The findings may also explain why some people feel better on low-FODMAP diets. These diets reduce the sugars that gut bacteria use to produce short-chain fatty acids. With fewer fatty acids, the L cells are less likely to activate this pain pathway, leading to fewer serotonin spikes and less pain.

Finally, the study helps explain why IBS symptoms often worsen or improve with hormonal changes. Still, estrogen alone is not the whole story. Not every woman develops IBS. Other factors — such as genetics, diet, infections, or stress at a critical time — likely combine to trigger the condition.

Together, these findings provide strong biological evidence that women’s gut pain is real, complex, and worthy of serious medical attention.

Sources of information:

- A. Venkataraman et al. A cellular basis for heightened gut sensitivity in females. Science. Published online December 18, 2025. doi: 10.1126/science.adz1398.

- J.R. Bayrer et al. Gut enterochromaffin cells drive visceral pain and anxiety. Nature. Published online March 22, 2023. Doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05829-8