The samples reveal, among other things, that the moon was still volcanically active more recently than previously thought.

Do you remember the Chang’e 5 mission? This Chinese spacecraft took to the skies in late November 2020 and headed for the moon in a few days, before landing in Oceanus Procellarum (an area of solidified lava from an ancient volcanic eruption). Not only did Chang’e 5 land on the moon in one piece, he also took some samples that he delivered safely to Earth. Now, researchers have delved into these prestigious lunar monsters. And that leads to some interesting discoveries.

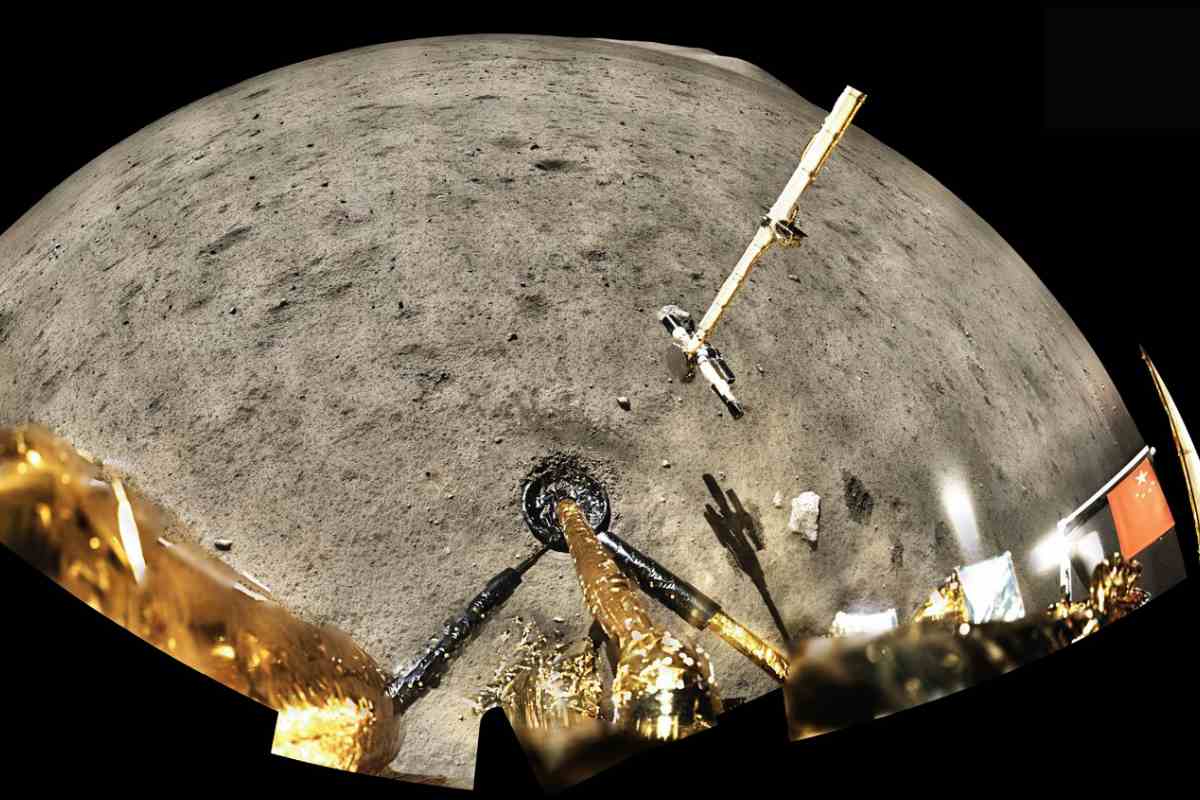

China’s Chang’e 5 mission had a clear goal: to explore the moon. Change’e 5 consisted of four parts: an orbiter with the return capsule and a lander with an ascent stage. In addition, Change’e 5 was equipped with cameras, a robot arm and a real ‘sampling scoop’. As mentioned, the craft took to the skies at the end of November aboard China’s own Long March launcher. In six days, the probe headed for the moon, where it successfully orbited our natural satellite. After it appeared that all systems were functioning properly, it was soon time for the next step. The landing module and lander disengaged and descended to the lunar surface. In the end, Change’e 5 managed to land successfully on the Mons Rümker mountain; a remote volcanic formation located in the northwestern part of the moon’s face. Using a robotic arm, the lander then scooped up some surface material. Slightly deeper material was also collected with the help of a drill. The collected material was then vacuum stored in a special capsule. The lander then detached itself from the lunar soil and rejoined the Chinese orbiter, which was still in orbit around the moon. Change’e 5 then set course for Earth again, where it landed safe and sound again in December.

An international team of researchers has now subjected the delivered package from Change’e 5 to a thorough inspection. A momentous moment. Because they are the first fresh samples of the moon to be examined after more than 40 years.

Age

First, the team attempted to determine the age of the lunar samples. And now they come with the happy news that the lunar samples brought back (made up of rock and debris from the volcanic formation) are a sloppy two billion years old. That works out surprisingly well. “The age of the volcanic rock brought by the Apollo missions has been estimated at 3 billion years old,” said study researcher Brad Jolliff. “And all the impact craters that are age-determined are younger than 1 billion years.” It means that the Chang’e-5 monsters are filling a critical void. “It’s the perfect monster to fill a gap of more than 2 billion years,” Jolliff said.

Volcanic Active

At the same time, this means that the moon was still volcanically active more recently than previously thought. The analyzed rock is formed from magma that was spewed about 2 billion years ago. And that’s more recent than other known volcanic lunar samples. According to the researchers, there must have been a heat source in the region to explain this late volcanic activity. However, they found no evidence of high concentrations of heat-producing radioactive elements in the moon’s deep mantle; something that was suggested before. The researchers will therefore continue to look for alternative explanations and, for example, study the possibility of tidal heating.

Craters

Incidentally, the findings are important not only for our understanding of the moon, but also for studying other rocky planets in the solar system. “Planetary scientists know that the more craters on a surface, the older it is,” explains Jolliff. “The fewer craters, the younger the surface. But to be able to make more definitive statements about that, you need to have samples of those surfaces.” Scientists have used the moon’s permanent craters to estimate the ages of various regions on its surface, based in part on how many craters there are in the area. But now that we know with great accuracy the age of the lunar samples brought by Chang’e 5 (and thus the area in question), this information could help improve the technique for dating other planetary surfaces.

All in all, the study not only provides answers, but also raises new questions. For example, the researchers now plan to study how magma formed about 2 billion years ago. Ultimately, the researchers hope to reveal more and more secrets about our moon with the lunar samples.

Source material:

“Samples returned by Chang’e-5 indicate late volcanism on the Moon– AAAS (via EurekAlert)

“Chang’e-5 samples reveal key age of moon rocks– Washington University at St. Louis (via EurekAlert)

“Dating the youngest rocks ever found on the Moon– Curtin University (via Scimex)

Image at the top of this article: