Currently, a previous infection by the dengue virus protects people against the Zika virus. But the question is whether that will remain the case, American researchers say.

While everyone hopes that no new variant of the coronavirus will emerge that will kickstart the entire pandemic, there are of course other viruses that can cause problems. For example, the Zika virus, which caused an epidemic in South America in 2015. American researchers led by Pei-Jong Shi (University of Texas Medical Branch) and Sujan Shresta (La Jolla Institute of Immunology) now have established that this virus is only a single mutation away from a worrying variant.

Same family

The Zika virus, which is spread by mosquitoes, usually causes few problems in adults, but unborn children can suffer from abnormalities. For example, microcephaly, a condition in which the brain does not develop properly and the skull remains smaller.

‘Fortunately’, the virus mainly affects areas where the dengue virus is also common. And because both viruses belong to the same family – the Flaviviruses – a previous dengue infection protects against Zika infection.

At least… If the virus stays as it is. As we now know all too well due to the corona crisis, viruses can mutate. And then the question is whether the Zika virus in dengue area remains so harmless.

pregnant mice

To investigate this, Shi, Shestra and colleagues passed the Zika virus in the lab first through a mosquito cell and then through a mouse cell. They repeated that ten times, to simulate how the virus moves from host to host.

They injected the virus that they got in this way into pregnant mice. It made them sick, even if they had previously become ‘immune’ by the dengue virus. In addition, the amount of viruses was greater in both immune and non-immune mice.

The researchers then determined which mutation had occurred in the virus. They incorporated this mutation into a Zika virus, with which they subsequently infect, among other things, brain stem cells from a human fetus. After that infection, they turned out to have produced many more viruses than cells infected with the ‘normal’ Zika virus.

Increasing threat

The place in the DNA where this mutation is located, the researchers call a “hotspot for mutations that can exacerbate disease transmission and disease severity”. As far as the researchers are concerned, Zika viruses must therefore be closely monitored so that mutations at this location are quickly identified.

Also Martijn van Hemert, virologist at the Leiden University Medical Center, advocates keeping an eye on these types of viruses. “Before I had to focus on the coronavirus with almost my entire research group, we mainly worked on viruses that are transmitted by insects, such as the Zika virus,” he says. “Before covid, I honestly expected one of these viruses to be the first to make the news. With the advance of the tiger mosquito in Europe, climate change and increasing globalization, these viruses are an increasing threat, also in our country.”

“A mutation comparable to the mutation described in this lab study has already been found in patient samples,” continues Van Hemert. “It is therefore very important to properly monitor – and combat the Zika virus and this variant!”

Source material:

†A Zika virus mutation enhances transmission potential and confers escape from protective dengue virus immunity” – Cell Reports

†A small mutation can make Zika virus even more dangerous” – La Jolla Institute for Immunology

Virologist Martijn van Hemert (LUMC)

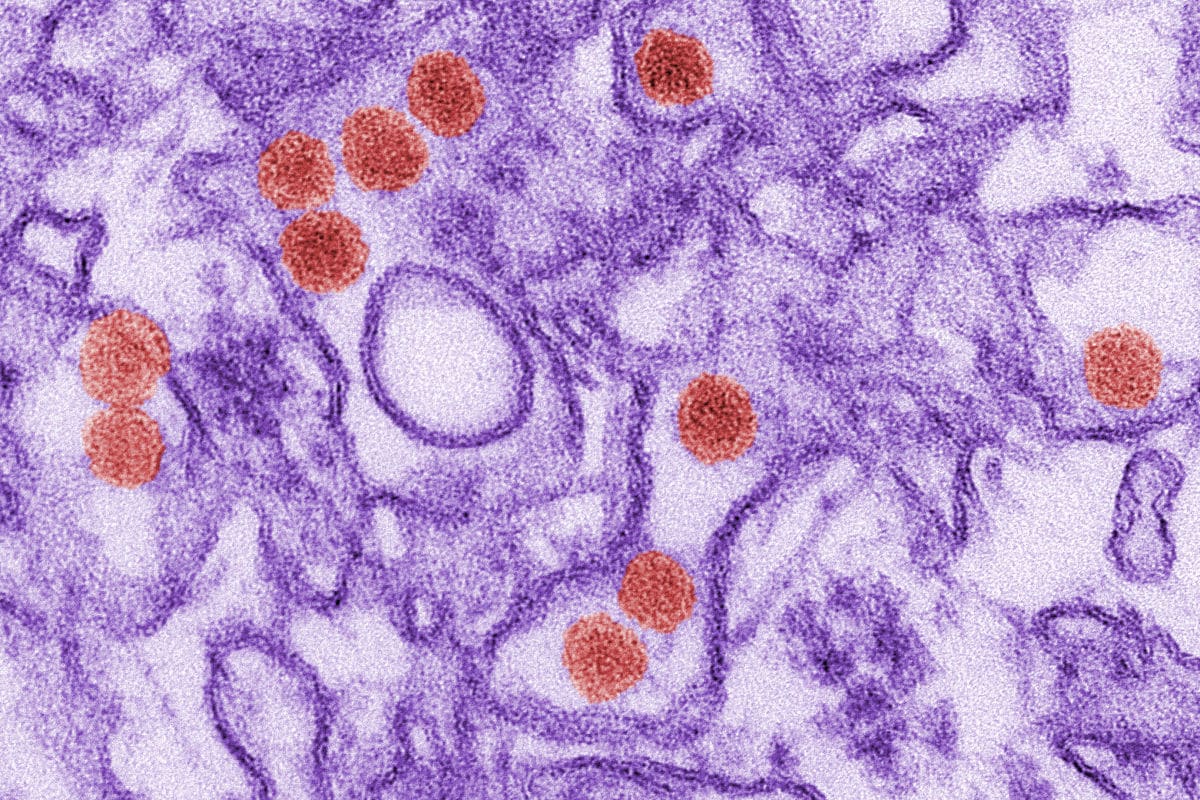

Image at the top of this article: CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith