In the Alps, at an altitude of 2800 meters, researchers have found remarkably large remains of three different ichthyosaurs. And that raises an interesting question: Did these swimming reptiles get much bigger than we thought possible?

The finds are presented in the magazine Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology† The study deals with a tooth from an ichthyosaur – a now extinct swimming reptile – that was found high in the Swiss Alps somewhere between 1976 and 1990 (see box). An analysis of the tooth now shows that it is really gigantic – also compared to teeth of other oversized ichthyosaurs. For example, the root of the tooth is three times as thick as the largest root previously recovered from an ichthyosaur.

Tooth

For now, though, we’ll have to make do with the tooth — and a few other interesting ichthyosaurs remains that were discovered in the last century and were forgotten until researchers recently pulled them back from the dust and studied them more closely. The recovered tooth particularly appeals to the imagination, says Sander. “The root has a diameter of 60 millimeters. The largest root found in a complete skull until recently was 20 millimeters wide and came from an ichthyosaur that was almost 18 meters long.” If the tooth now central to the new study can provide any indication of the size of the ichthyosaur it belonged to, then that specimen must have been significantly larger. Possibly even larger than the largest ichthyosaur known to us until recently, the Canada-discovered 21-meter-long Shastasaurus sikkanniensisthe researchers say.

At the same time, they have to be careful; it is actually impossible to estimate the size of an ichthyosaur based on a tooth alone. “It’s difficult to determine whether the tooth came from a large ichthyosaur with huge teeth or from a giant ichthyosaur with medium-sized teeth,” Sander admits.

Not much bigger

It is not immediately obvious that the ichthyosaur to which this tooth belonged was significantly larger than S. sikkanniensis† And that has everything to do with the fact that it had teeth. Scientists believe that reaching extreme size and a predatory lifestyle (which requires teething) don’t mix. That is why the largest animal of our time – the blue whale – is toothless. With a size of thirty meters, the blue whale clearly makes the sperm whale (the largest modern animal with teeth) pale. And that can be traced back to their diet; whereas the blue whale swallows water quite passively and filters out small, tasty animals, the sperm whale is a real hunter. However, the latter also means that it burns a lot of calories in the search for and hunting for food. “Marine predators therefore probably cannot grow much larger than a sperm whale,” says Sander. Hence, the researchers also believe it is certainly possible that the huge tooth now discovered in the Swiss Alps did not belong to a record-breaking large ichthyosaur, but to an average ichthyosaur with giant teeth.

The tooth of the ichthyosaur, of which the root is preserved, but the crown is only partially preserved. Image: © Rosi Roth / University of Zurich.

Even more leftovers

That said, the research does caution that the record-breaking S. sikkanniensis had European relatives approaching the Canadian giant in size. This is further supported by a second finding that the researchers present in their study. It is a vertebra with ten rib fragments, which in turn belong to a different ichthyosaur than the one that left the remarkably large tooth behind. A comparison of this vertebra and rib fragments with similar remains of other better-preserved ichthyosaurs suggests that it probably grew to be about 20 meters long when alive.

If the estimates — which are certainly somewhat complicated by the fact that the rock layers have been crushed by tectonic activity — are correct, the oversized ichthyosaurs recovered in the Alps may have been the last of their kind. “Only the ichthyosaurs the size of medium and large dolphins and orca-like shapes survived into the Jurassic,” Sander said.

Mystery

Those dolphin-like ichthyosaurs managed to survive for millions of years, but eventually died out about 90 million years ago. Today, both those last dolphin-like forms and their gigantic ancestors are still shrouded in mystery. And of the large ichthyosaurs – which could grow to be at least 20 meters long and weigh an estimated 80 tons – fossil remains are rarely found. “Why that is is a mystery to this day,” says Sander. It makes the finds in the Swiss Alps very valuable; After remains of large ichthyosaurs were previously found mainly in North America, and later appeared in the Himalayas and New Caledonia, there is now also evidence that the giants were allowed to call today’s European continent their home. At the same time, many questions remain unanswered even after these finds. For example, it remains shrouded in mystery how large ichthyosaurs could become.

It’s almost frustrating. Because although bones have been found in Great Britain and New Zealand, for example, that indicate that some ichthyosaurs could grow to be as large as blue whales, it is difficult to prove that. For a moment it seemed that they had the key in their hands in 1878, when a 45 centimeter wide vertebra of an ichthyosaur was described; but the bone appears to have been lost at sea en route to London. The tooth discovery — which in itself also gently hints that ichthyosaurs grew much larger than we thought possible — fits in with that trend; decisive evidence for the existence of ichthyosaurs much larger than S. sikkanniensis does not happen even after climbing in the Swiss Alps. “It all adds to the enormous embarrassment within paleontology that, despite the exceptional size of their fossils, we know so little about these giant ichthyosaurs. We hope to change that and soon find new and better fossils.”

Source material:

†Giant marine reptiles at 2,800 meters above sea level” – University of Bonn

†Huge new ichthyosaur, one of the largest animals ever, uncovered high in the Alps” – Taylor & Francis Group

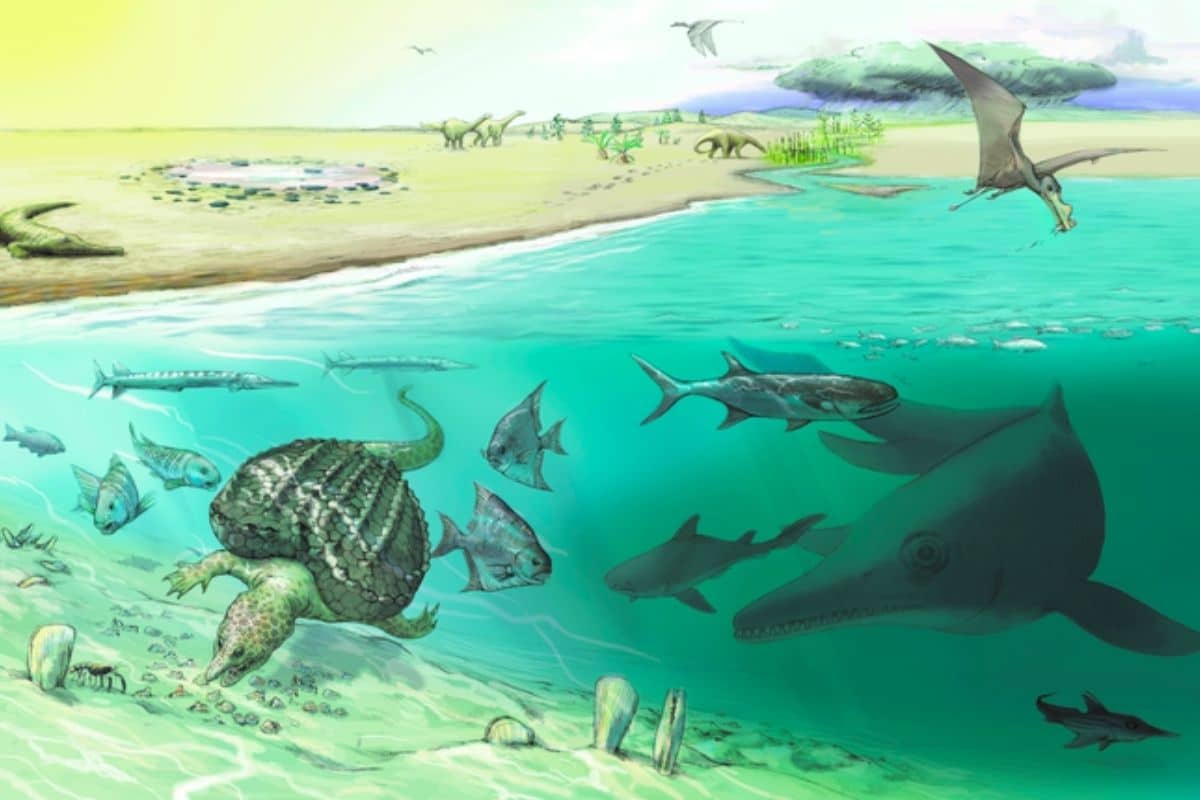

Image at the top of this article: © Jeannette Rüegg / Heinz Furrer, University of Zurich