And with that, the risks have been reduced considerably in the past two weeks, because shortly before launch there were still 344 points where the mission could go wrong.

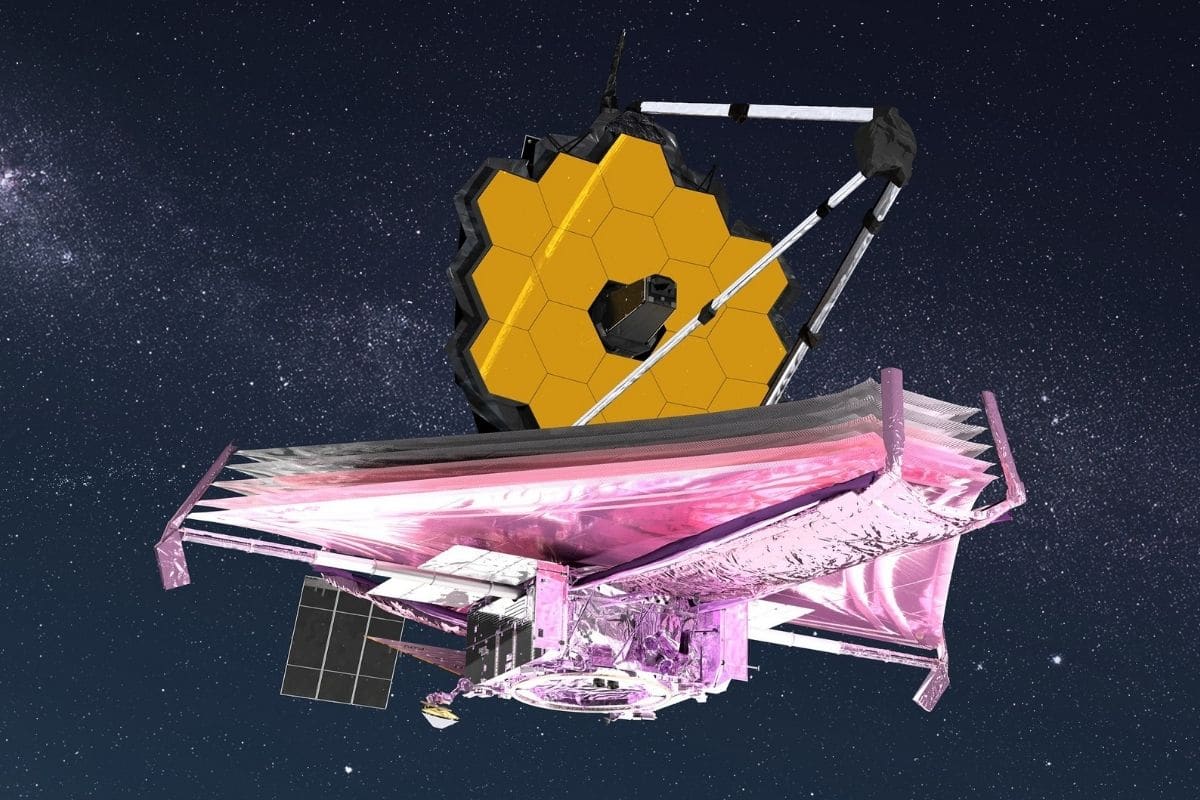

There was great relief when James Webb unfolded the last part – the main mirror – last Saturday and finally took its final shape after 14 days of origami-in-space. And that relief was certainly not misplaced, because after building the most powerful and complex space telescope ever, correctly unfolding that telescope in space was the biggest challenge.

From 344 critical points…

And it was certainly not self-evident that the telescope – after it had freed itself from the relatively cramped Ariane 5 rocket – would unfold effortlessly. As many as 344 things could go wrong from launch to end of the mission, the James Webb mission team said before the mission. And the lion’s share of those potential times when things could go wrong came in those first two weeks after launch, which is when the telescope was unfolding.

…to 49

That period is now behind us. James Webb is unfolded and well on his way to the final destination: Lagrange point 2. This naturally raises the question of what the risks are now. How many of those 344 moments when things could possibly go wrong are left? The redeeming answer came at a press conference last weekend, through Mike Menzel, a member of the James Webb mission team. It can still go wrong on 49 points. And we are not going to cross out much of that anymore; most of the risks will persist until the end of the mission.

That it can still go wrong on 49 points may seem a bit scary, but Menzel likes to put it into perspective during the same press conference. He points out, for example, that every mission is confronted with such a number of risks. In addition, 15 of the 49 risks are related to specific instruments. It means that when disaster strikes in those 15 cases, it does not immediately mean the end of the mission, but it may only have consequences for the functioning of those instruments concerned.

To L2

The fully expanded James Webb is currently on his way to his final destination: Lagrange point 2. From that point, the most powerful space telescope ever built will conduct research into (potentially habitable) exoplanets, the first galaxies and the formation of stars and planets. James Webb – who is already more than 1.1 million kilometers from Earth – is expected to arrive in L2 in just three weeks. To get there, the telescope’s thrusters still have to be cranked twice for minor course corrections. In addition, about 29 days after launch, a third ‘burn’ is needed to place the telescope in L2. “That’s a small burn,” says Menzel. “And we are not worried about that – certainly in view of previous ‘burns’ that we have already successfully completed.”

First images are waiting

After James Webb arrives at the destination, engineers need about 5 months to calibrate the instruments and align the mirror segments so that they function together as one large mirror. That time is also needed to allow the telescope to cool down further; the telescope must be very cold to be able to observe the infrared light from faint, distant objects. The first observations are therefore not expected until the end of June.

Prior to the launch, James Webb was expected to do at least five years of research. And it was the hope that the telescope would last 10 years. Shortly after launch, it became apparent that the Ariane 5 rocket placed the telescope in the desired orbit so accurately that only minimal course corrections were required and significant fuel savings were achieved. This would give James Webb, ESA and NASA announced at the end of December, enough fuel to remain operational for at least 10 years. Researchers have now obtained an even more accurate picture of James Webb’s fuel consumption and the forecast has been revised again; according to the latest calculations, the telescope – which has already cost 10 billion dollars – should be able to last at least 20 years based on the amount of fuel left.

Source material:

“News Update on James Webb Space Telescope’s Full Deployment” – NASA

Image at the top of this article: NASA