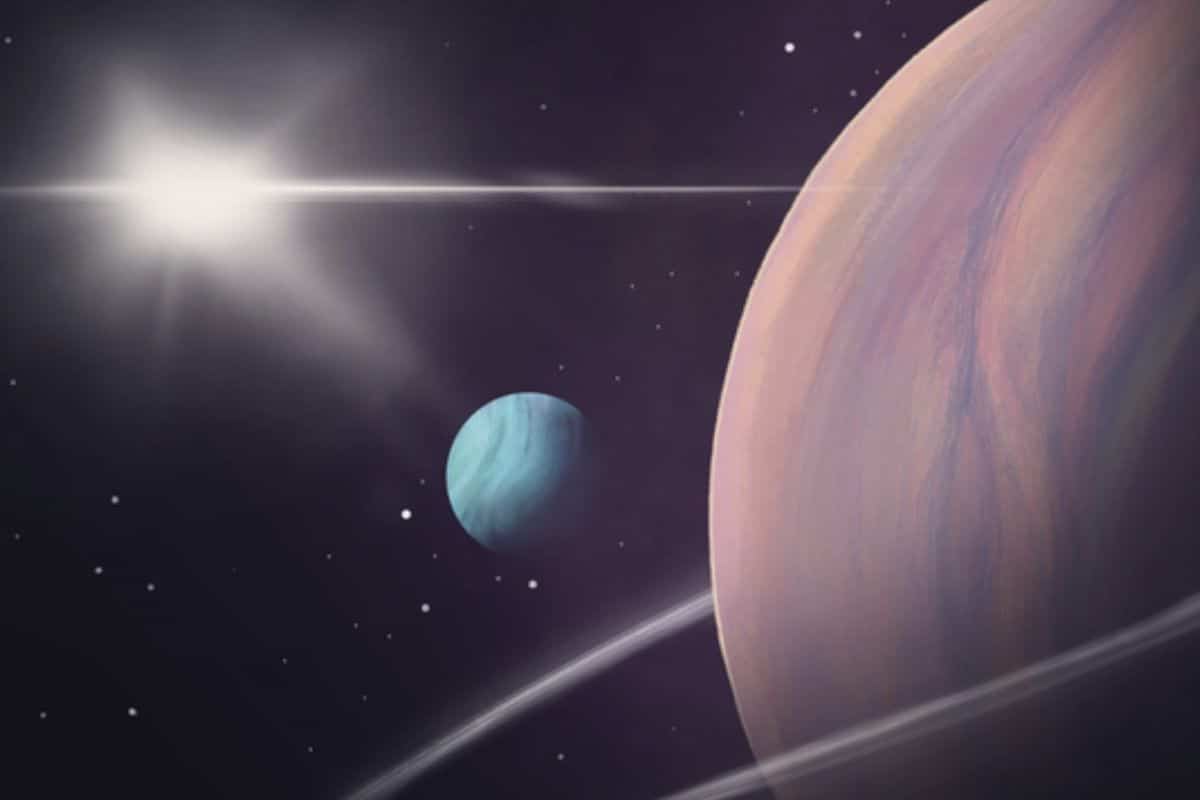

An exoplanet Kepler 1708b may be circling 5,500 light-years from Earth.

In recent years, astronomers have discovered thousands of candidate exoplanets. And from what we see in our own solar system, you would expect that quite a few of those exoplanets also revolve around moons. But evidence for this is lacking to date. “Exomoons are expected to be small and their signals are quickly overshadowed by those from the much larger planet they orbit around,” said researcher David Kipping. Scientias.nl from. “That makes it much more difficult to find exomaniacs. Moreover, much less money and resources are available for this kind of research than for the search for planets.”

Kepler-1708b-i

And yet Kipping and colleagues now think they are on the trail of an exomoon. It would be a large specimen that has been christened Kepler-1708b-i for the time being. The moon is said to be 2.6 times larger than Earth and orbits the exoplanet Kepler-1708b, which in turn can compete in size with Jupiter.

Method

The astronomers tracked down the candidate exomaniac when they looked over gas giants discovered by the Kepler space telescope using the transit method (see box). They specifically focused on 70 exoplanets that had a long orbital period and were therefore at a considerable distance from their parent star. This choice was partly inspired by the fact that in our solar system we find a lot around the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, situated at a considerable distance from the sun; together, these planets are home to more than 100 moons. So many moons could not be found around the 70 Kepler planets; in the end, only one signal was found in the Kepler data that tentatively hinted at the presence of an exomane.

The Kepler space telescope has discovered thousands of (candidate) exoplanets using the transit method. The space telescope stared at stars for a long time, hoping to witness their luminosity decreasing regularly. Such a regular dip in brightness may indicate the presence of a planet that, as it orbits the parent star, periodically intersects between the parent star and Kepler, briefly blocking out a very small portion of the star’s light. For this new study, the scientists re-examined the light curves that had previously revealed the existence of 70 gas giants, hoping to find some indication that one or more of those planets had passed their parent star accompanied by an exomoon. moved.

For now, Kepler-1708b-i will go down in the books as a candidate exomaniac. This means that although there are indications that the moon exists, this has not yet been proven. More observations are needed to confirm the existence of Kepler-1708b-i, Kipping emphasizes. “Kepler is no longer operational, so we can no longer monitor the candidate exomaniac using the same telescope. But we can use the Hubble or James Webb space telescope to look at it again.” However, we should not expect a definitive answer in the short term. “We have to wait until March 2023 anyway, when the planet will pass in front of the parent star again.”

fluctuations

Kipping is hopeful that the exomoon’s existence can be confirmed sooner or later. But not everyone is convinced. “It could also just be a fluctuation in the data,” said astronomer Eric Agol (not involved in the study). And it must be admitted: that is certainly not inconceivable. For example, the signal that hints at the presence of an exomoon could also be the result of changes in or on the parent star. But that chance is small, according to Kipping. “Stars are not perfect light sources; due to all kinds of effects on the star’s surface and below, their brightness fluctuates slightly over time and that manifests itself in our data as well. But we have calculated that the chance that we mistake such fluctuations for an exomoon is about 1 percent.”

Originate

The future must show whether a large moon orbits around Kepler-1708b. If the existence of the candidate-exomaniac is indeed confirmed in the coming years, this will almost automatically lead to many new questions. For example, the moon poses a significant challenge to the theories that astronomers now use to describe the formation of moons. “All theories about moon formation are based on what we see in our own solar system,” Kipping said. “A large moon (such as Kepler-1708b-i, ed.) presents a challenge to those current theories because we simply don’t see such large moons in our solar system.” However, it is not to say that large moons like the alleged Kepler-1708b-i are inexplicable. “Physically speaking, it’s possible to think of ways in which such large moons could take shape.” It is thus possible that Kepler-1708b-i originated in the same way as planets and could also have grown into a sizable gas giant, but was captured somewhere halfway by another, much larger, planet – such as Kepler-1708b – and from that moment was doomed to live like a moon.

Kepler-1708b-i is not the first candidate exomane presented by Kipping and colleagues. In 2017 they also came up with a candidate exomaniac. It would orbit the Jupiter-like planet Kepler-1625b and be even larger than Kepler-1708b-i. However, the existence of that exomoon has not yet been confirmed. It doesn’t stop Kipping from continuing to search. He would like to remind us that not so long ago people were quite skeptical about the existence of exoplanets. But now we are hardly surprised by the news that another exoplanet has been discovered. It remains to be seen whether things will go just as quickly with the exomoons. But Kipping is once again optimistic. “My team has developed several new methods over the past year that we think are going to shake things up a bit. And of course we are also very enthusiastic about the potential of the James Webb telescope.”

Source material:

“Astronomers find evidence for a second supermoon beyond our solar system– Columbia University (via Eurekalert)

Interview with David Kipping

Image at the top of this article: Helena Valenzuela Widerström