The bacteria may be more vulnerable than previously thought. And that’s good news.

Scientists of the University College London have created super-sharp images of a gram-negative bacterium. The images will go down in the books as the sharpest images ever made of a living bacteria and give us a detailed picture of the ‘skin’ of these bacteria. And guess what? It may not be as impenetrable as you might think. That can be read in the magazine Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Gram-negative bacteria

The study revolves around so-called gram-negative bacteria. These are bacteria that are equipped with a protective outer layer. This so-called membrane is difficult to penetrate and the main reason that various gram-negative bacteria are not very interested in antibiotics. “This outer membrane is a great barrier to antibiotics and an important reason why some bacteria are resistant to medical treatment,” said researcher Bart Hoogenboom. “But it remains relatively unclear how that barrier works, so we decided to study it in detail.”

Feeling shape

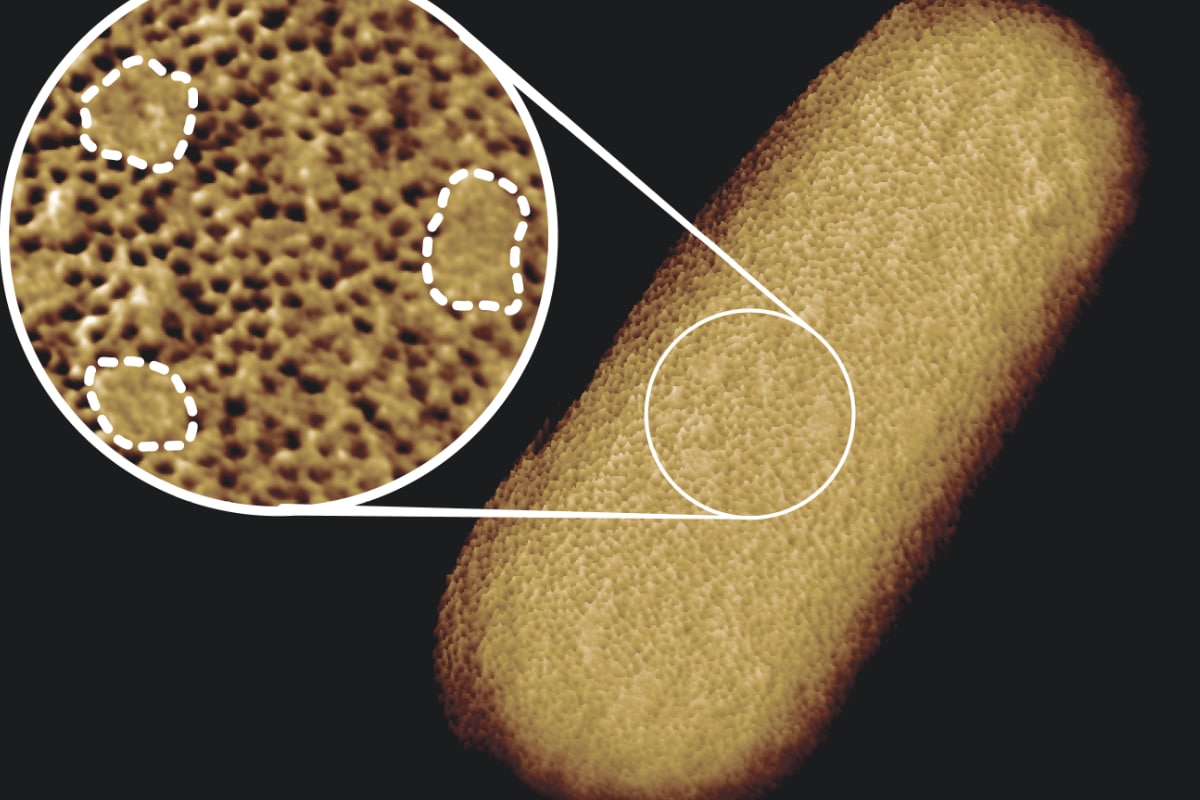

To get a better picture of the membrane of these gram-negative bacteria, the scientists started working with the well-known bacterium Escherichia coli. They took a tiny needle and let it slide over the living bacteria in order to ‘feel’ its shape. Because the tip of this needle was only a few nanometers wide, the researchers were able to ‘feel’ even tiny structures on the surface of the bacterium. And by touching the bacterium in this way, the researchers were also able to draw out that outer membrane in great detail. It results in the sharpest images we have of a living bacterium and a surprise.

“The images of the outer membrane of bacteria that you find in books show that the proteins are disorganized and mixed with other building blocks of the membrane,” said study researcher Georgina Benn. But in reality, the membrane turns out to be very different. It appears to consist of dense networks of proteins interspersed here and there by regions that do not harbor proteins, but are enriched in glycolipids; molecules with sugar chains that hold the outer membrane taut. An important discovery, says Hoogenboom. “It suggests that this barrier is not equally impenetrable everywhere and does not spread over the entire bacterium, but has strong and weak spots.”

Here you can see that the membrane consists of closely packed protein networks. But these networks are interspersed here and there with protein-free islets (covered with a dotted line in the image). Image: Benn et al. UCL.

Cracks in the armor

Benn compares the protein-poor spots in the membrane with cracks in the bacterium’s armor. “We can now investigate whether and how this arrangement in the membrane influences the function and integrity of the membrane and the resistance to antibiotics.” And hopefully it will eventually lead to researchers being able to use the weak spots in the membrane to combat gram-negative bacteria that are now difficult to fight, armed with antibiotics.

The research also provides more insight into how gram-negative bacteria can grow super fast, in no way hindered by that tough membrane. so can E. coli multiply in 20 minutes under ideal conditions. It has everything to do with those glycolipid-filled islets in the sea of proteins. These ‘islets’ make the membrane much more elastic than it would be if it consisted entirely of networks of proteins. And thanks to this elasticity, the bacteria can grow quickly, without losing their ‘armour’.

Source material:

“Sharpest images ever reveal the patchy face of living bacteria– University College London (via Eurekalert)

Image at the top of this article: Benn et al. UCL