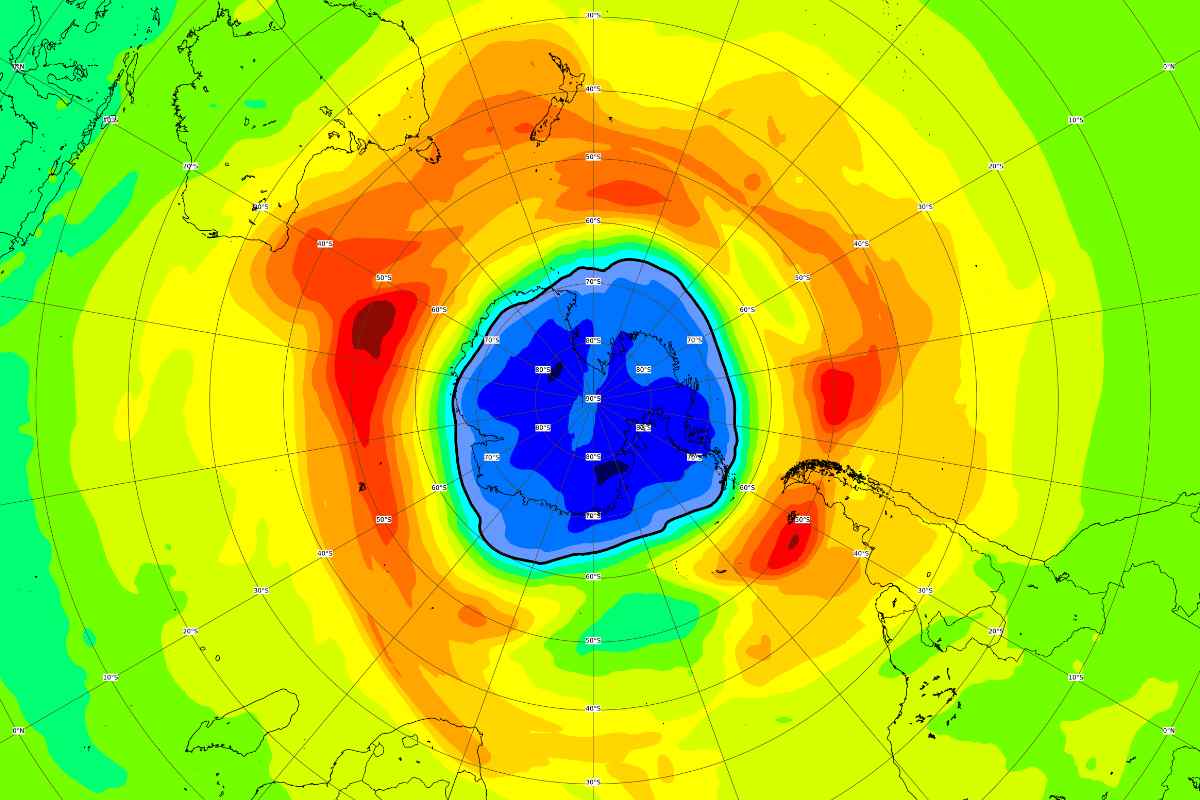

The hole is already bigger than Antarctica itself.

The ozone layer is located in the stratosphere – at an altitude of about 40 kilometers. This protects us against harmful UV radiation and is therefore very important. However, every September, during the Australian spring, a ‘hole’ forms in the ozone layer. And this recurring gap is extraordinarily large this year.

During the spring season in the southern hemisphere, the famous ozone hole forms over Antarctica every year. This is not a real hole, by the way, but a continuous thinning of the ozone layer. The hole reaches its maximum size between mid-September and mid-October. Then, when temperatures begin to rise high in the stratosphere in late spring in the Southern Hemisphere, ozone depletion slows and the polar vortex weakens. As a result, the hole in the ozone layer is slowly but surely shrinking, until it completely disappears by December.

Researchers are closely monitoring the development of the hole. And after a fairly standard start, the ozone hole has grown significantly over the past week. The hole is now 23 million square kilometers in size, making it even larger than Antarctica itself.

big hole

“At the start of the season, the ozone hole developed as we expected,” said Vincent-Henri Peuch, director of Copernicus atmospheric monitoring service CAMS. “It’s very similar to last year when the hole didn’t have an exceptional start either, but later in the season turned into one of the longest lasting ozone holes in our database. Now our forecasts show that this year’s gap has evolved into a slightly larger gap than usual. The vortex is quite stable and the stratospheric temperatures are even lower than last year. We are looking at a fairly large and possibly deep ozone hole.”

Size of the ozone hole in 2021. Image:

contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2021), processed by DLR

Last year’s hole

So it seems like history is repeating itself. Last year’s ozone hole over Antarctica had eventually grown into one of the largest and deepest in recent years. The gap grew rapidly from mid-August, reaching a peak of approximately 25 million square kilometers on October 2. The large ozone hole was powered by a strong, stable and cold polar vortex that kept the temperature of the ozone layer over Antarctica consistently cold. This was in stark contrast to the unusually small ozone hole that formed in 2019. But also this year it seems that the gap will be unusually large. “The course of the ozone hole in the coming months will be extremely interesting,” notes researcher Antje Inness.

recovery

Still, it appears that the hole in the ozone layer is recovering. This is mainly due to the Montreal Protocol, which was established in 1987 and has been labeled as one of the world’s most successful environmental agreements. The Montreal Protocol – which was signed by 200 countries – is intended to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production and consumption of harmful substances (see box).

CFCs are long-lived chemical compounds that have been widely used in the production of refrigerants, aerosols, chemical solvents and building insulation. When emitted, the chemicals can rise to the stratosphere. Here they are broken down by the ultraviolet radiation of the sun, releasing chlorine atoms. These atoms destroy ozone molecules. And that’s bad news, because ozone protects life on our planet by absorbing potentially harmful ultraviolet radiation. For example, the UV radiation can cause skin cancer and cataracts and damage the flora. To deal with CFCs, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol for short) was created. Governments promised to reduce the production of substances that damage the ozone layer. And meanwhile, the so-called ‘hole in the ozone layer’ is indeed recovering.

Since the ban on halogenated hydrocarbons, the ozone layer has shown signs of recovery. But it is a slow process. Scientists predict that it will be at least 2060 or even 2070 before the ozone-depleting substances are completely eliminated. That’s because some of the ozone-depleting substances emitted by human activities linger in the stratosphere for decades. Therefore, according to the researchers, it is essential to continue monitoring to ensure that the Montreal Protocol is enforced.

Source material:

“Copernicus: Southern Hemisphere ozone hole surpasses size of Antarctica” – Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service

“What’s going on with the ozone?” – ESA

Image at the top of this article: Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service/ECMWF