Earlier this month, the Conger Ice Shelf – slightly smaller than the province of Utrecht – completely disintegrated off the coast of East Antarctica. A pretty unpleasant surprise.

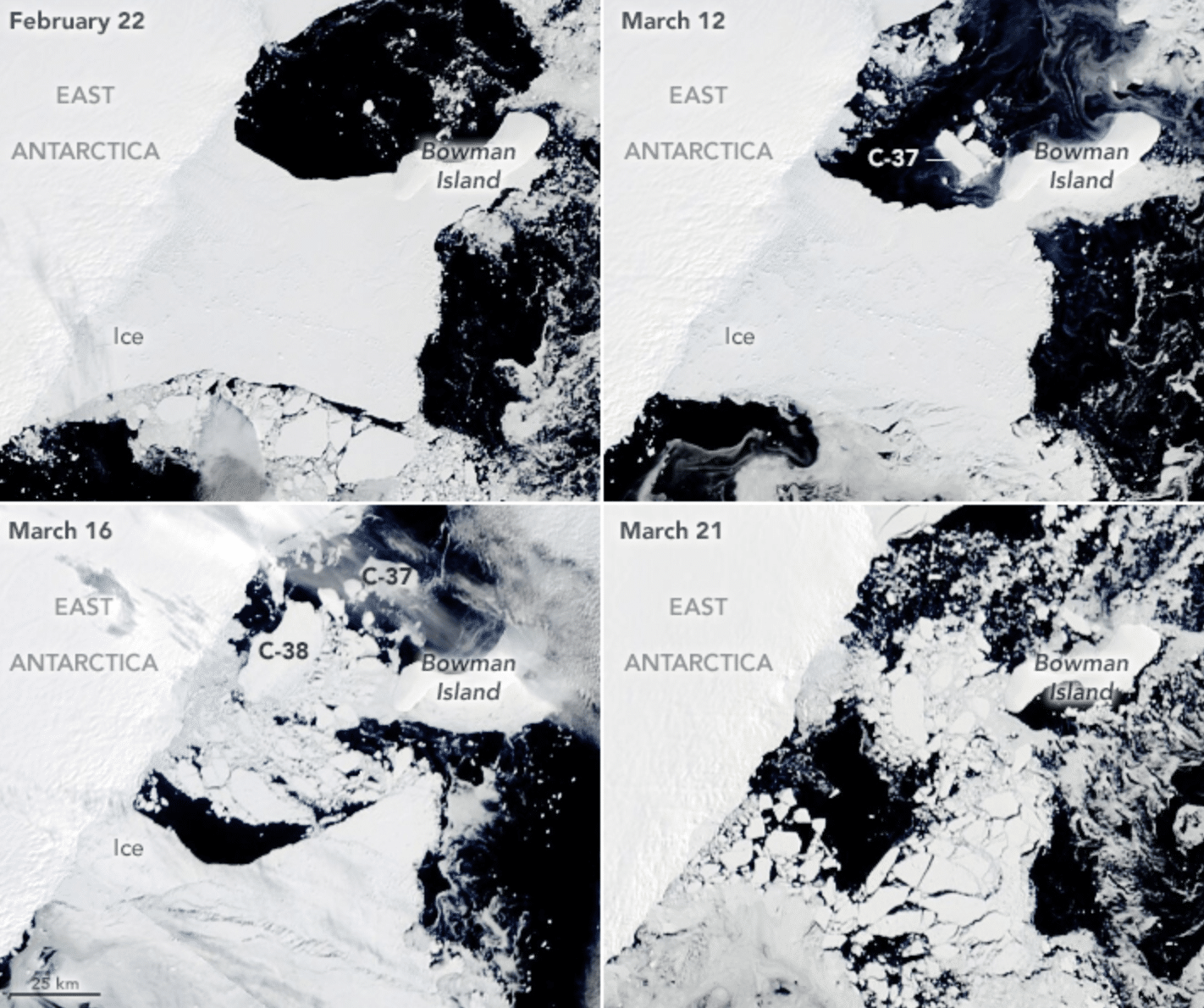

Nobody expected it, but it happened this month: the Conger Ice Shelf, off the coast of East Antarctica, has disintegrated. It all started around March 12; the ice shelf then gave birth to a sizable iceberg that was named C-37. A few days later, another huge amount of ice came loose. And barely a week later, the ice shelf – which with an area of about 1200 km2 is slightly smaller than the province of Utrecht – completely disintegrated.

It was an eventful month for the Conger Ice Shelf. First the ice shelf lost several pieces of ice and then it completely disintegrated. Images: NASA Earth Observatory, based on Landsat & MODIS data.

Surprise

It was all captured by satellites. And once researchers got their hands on the satellite images, they were quite surprised. “The collapse was surprising in the sense that no one saw it coming,” climatologist Stef Lhermitte, of the TU Delft, tells. Scientias.nl† It was well known that the ice shelf had been weakening for years in a row. “Satellite images show that the Conger Ice Shelf has been weakening and shrinking massively since the 1970s.” But even armed with satellite images and data, researchers are still unable to fathom the dynamics of such a languishing ice shelf to predict its collapse. “And that’s why it was a surprise now.”

Statement

By contrast, explaining the ice shelf collapse afterwards – again armed with those satellite images – is a lot easier. “To collapse an ice shelf you have to weaken the ice shelf (for example because it becomes thinner and more cracks appear or because a lot of meltwater collects on the surface) and these are often gradual processes that we have also seen for Conger for years. On the other hand, you need a trigger that creates extreme conditions so that the ice shelf eventually breaks. You can compare it with a tree that slowly weakens or sickens you until it falls over in a storm. We’ve seen both situations together for Conger. On the one hand you have the slow weakening, which is partly driven by climate change. On the other hand, you now had some kind of extreme conditions due to the atmospheric river over East Antarctica. We know that such atmospheric rivers can create situations that can lead to ice erosion. We still have to find out exactly how that works for Conger (and we’re working on that). I don’t think the temperatures really contributed as I didn’t see meltwater in the satellite images leading up to the instability, but the other extreme conditions may have played a role.” For example, the wind that accompanied the atmospheric river may have caused more wave movements that literally broke up the already weakened iceberg.

Effects

The breakup of the ice shelf in itself does not directly have significant consequences. For example, the melting of the icebergs that have formed will not lead to a higher sea level, because the ice shelf in its entirety already rested on the water. Indirectly, however, the disappearance of the ice shelf can cause ice behind it, located on land, to flow faster and dump more ice into the sea. After all, there is no longer an enormous mass of ice to counterbalance. But Lhermitte isn’t too worried about that right now. “Without an ice shelf, you expect the land ice to drain faster,” he confirms. “Now the Conger Basin is the smaller one in Antarctica anyway and the ice shelf was already weakening so I don’t expect any changes of magnitude, but it will be interesting to see what that means for the runoff in the future.”

East Antarctica

What worries researchers, meanwhile, is that the late Conger Ice Shelf was located in East Antarctica, a part of the South Pole that until recently was thought to be quite stable, unlike western Antarctica. In fact, in East Antarctica, until recently, people had never witnessed an ice shelf collapse. “It’s troubling because it shows[the collapse of the Conger Ice Shelf, ed.]that the sleeping giant, which is East Antarctica, might not be sleeping so soundly after all,” Lhermitte said.

It’s an alarming suggestion, given that East Antarctica could cause sea levels to rise five times faster than West Antarctica. “Although the Conger Ice Shelf was relatively small, it is one of the most significant collapses in Antarctica since the beginning of this century, when the Larsen B Ice Shelf disintegrated,” said glaciologist Catherine. Walker in a statement late last week. “And it’s probably a taste of what’s to come.”

So, while Lhermitte shares those concerns, he also feels it’s important to stress that it’s far too early to panic. Simply because we do not yet fully understand what is happening in East Antarctica. “I don’t think we should immediately fear a doomsday scenario for East Antarctica,” he said. In his view, the unexpected collapse of the East Antarctic Ice Shelf shows that there is still a lot of uncertainty about how this part of the continent will respond to a changed climate. “We need to understand and model the climate processes and the impact they have there much better.”

Source material:

†Ice Shelf Collapse in East Antarctica” – Earth Observatory NASA

†Scientists report complete collapse of East Antarctica’s Conger Ice Shelf” – WHOI

Interview with Stef Lhermitte

Image at the top of this article: NASA Earth Observatory, based on data from Landsat & MODIS