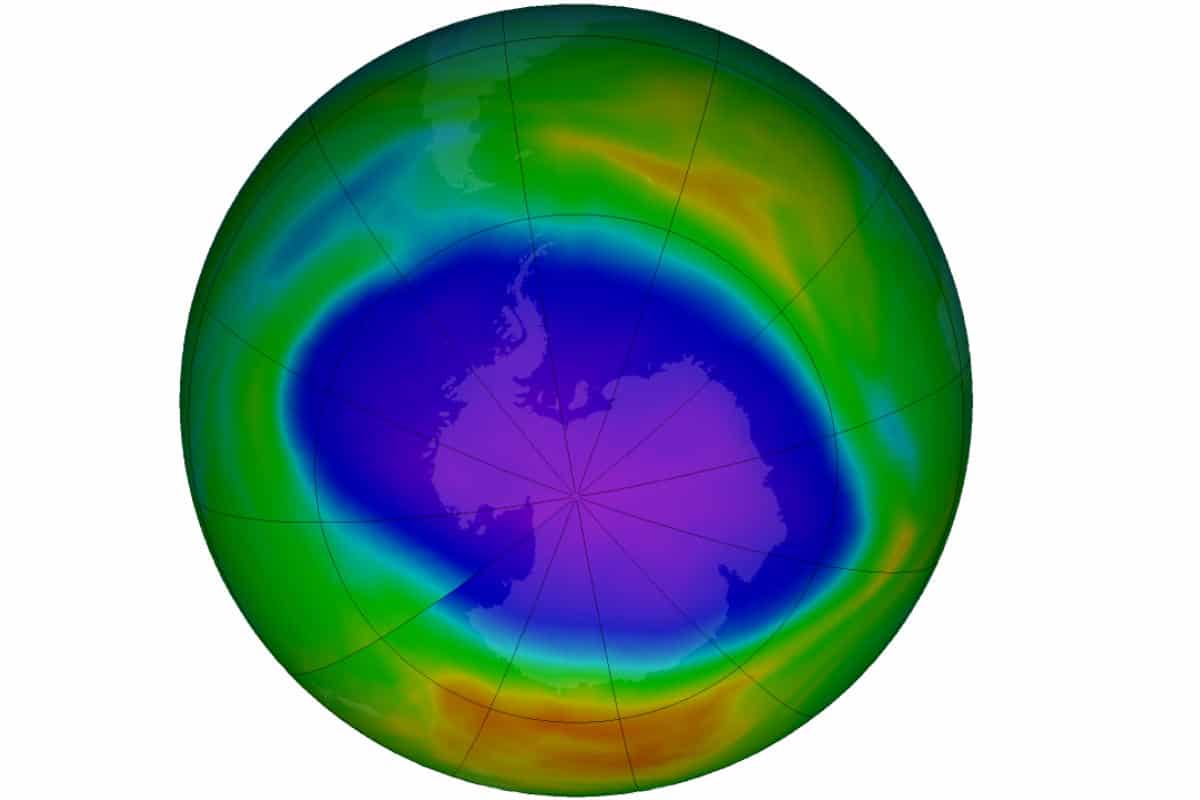

The ozone hole is now about the size of North America.

Every year between mid-September and mid-October, the ‘ozone hole’ reaches its maximum size. And this time too, the hole – just like last year – turns out to be exceptionally large and deep. For example, researchers now note a maximum size of 24.8 million square kilometers, equaling the size of North America.

Development of the hole

Researchers have been closely monitoring the development of the hole in the ozone layer for years. And this year – just like last year – something remarkable happened. At the start of the season, the ozone hole developed as expected. But in mid-September, the gap suddenly started an unprecedented growth spurt. The hole soon reached a size of 23 million square kilometers, making it even larger in size than Antarctica itself. The gap eventually grew slightly, reaching its maximum size of 24.8 million kilometers early this month, before shrinking again in mid-October.

Cause

Ultimately, the hole took 13th place in size since 1979. Why was the hole so exceptionally large and deep this year? Colder-than-average temperatures and strong winds in the stratosphere orbiting Antarctica have contributed to its large size, researchers say.

So it seems that history has repeated itself. Last year’s ozone hole over Antarctica had eventually grown into one of the largest and deepest in recent years. The gap grew rapidly from mid-August, reaching a peak of approximately 25 million square kilometers on October 2. At the time, the large ozone hole was also powered by a strong, stable and cold polar vortex that kept the temperature of the ozone layer over Antarctica constantly cold.

Montreal Protocol

Although the hole is larger than average this year, it is still significantly smaller than the ozone holes that appeared in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Many ozone holes in the 1990s and early 2000s were significantly larger than the ozone hole in 2021. Image: NASA’s Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens

This is mainly due to the Montreal Protocol. “Without the Montreal protocol, the gap this year would have been many times bigger,” emphasizes researcher Paul Newman. This protocol was established in 1987 and has been described as one of the world’s most successful environmental agreements. The Montreal Protocol – signed by 200 countries – aims to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of harmful substances – such as ozone-depleting chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs.

Slow process

Thanks to the agreement, the hole in the ozone layer is thus recovering. Although it is a slow process. Scientists predict that it will be at least 2060 or even 2070 before the ozone-depleting substances are completely eliminated. That’s because some of the ozone-depleting substances emitted by human activities linger in the stratosphere for decades.

Nevertheless, researchers are positive. If the atmospheric chlorine levels of CFCs were as high today as they were in the early 2000s, this year’s ozone hole would have been about 4 million square kilometers (!) larger under the same weather conditions.

Source material:

“2021 Antarctic Ozone Hole 13th-Largest, Will Persist into November” – NASA

Image at the top of this article: NASA Ozone Watch