The mission team wants to prevent the rover’s wheels from wearing out unnecessarily. And so a new route has been mapped out.

Mars rover Curiosity spent most of March climbing the so-called Greenheugh Pediment, a rugged sandstone escarpment. The rover briefly reached the north side of this hill two years ago, now it was the turn of the south side. Unfortunately, the Mars rover can turn around again. Because a large collection of razor-sharp wind boulders are blocking his way.

Greenheugh Fronton is a slope near the base of Mount Sharp that is about two kilometers wide. The Curiosity mission team first noticed this slope in orbital images before the rover landed on the red planet in 2012. The pediment is a striking ‘protrusion’. And so researchers wanted to better understand how it formed.

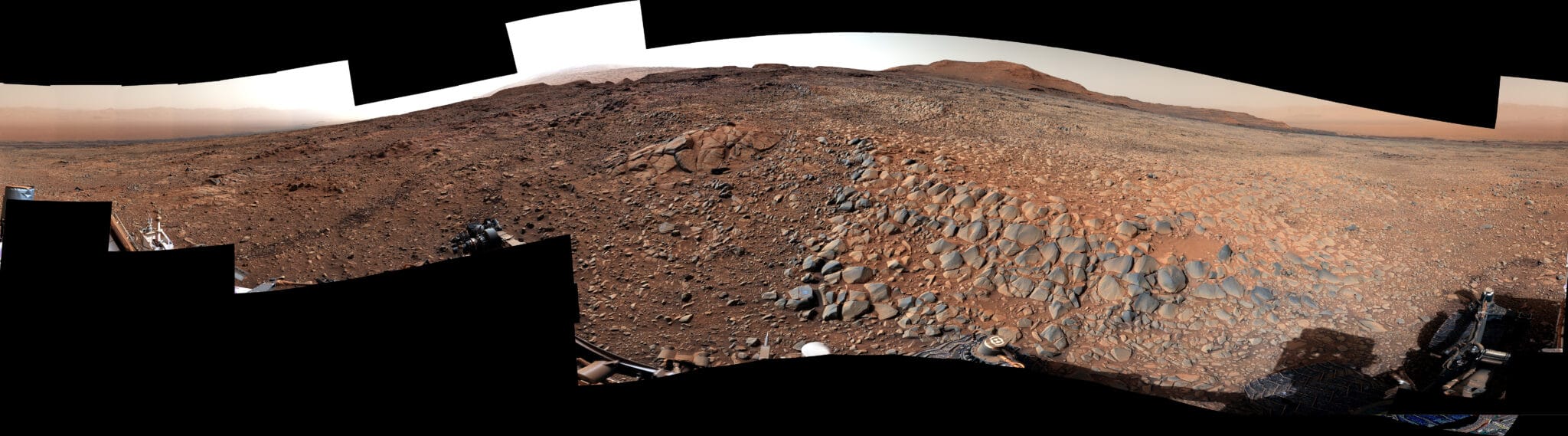

As Curiosity clambered up the slope, the mission team saw rather unexpectedly wind boulders looming, forming the surface of the Greenheugh Pediment. The team soon realized that the rover had better turn around. For example, the path for Curiosity was covered in more boulders than they’d ever seen in the rover’s ten-year mission. “It was clear that this wouldn’t be good for Curiosity’s wheels,” said project manager Megan Lin.

Not worth it

A wind boulder is a stone that has been ground down under the influence of wind and sand. The specimens Curiosity has encountered are made of sandstone, the hardest type of rock the rover has seen on Mars to date. Incidentally, the path up was not completely impassable for Curiosity. “It’s just not worth it,” NASA said. “As well as making the climb quite slow, it would also cause further wear on Curiosity’s wheels.”

The wind boulders seen through the eyes of Curiosity. Unfortunately, this means that the rover can turn around again. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Wind boulders have left marks on Curiosity’s tires earlier in the mission. Since then, engineers have found ways to slow wheel wear. The intention is that Curiosity will be around for a while. And so everything is done to keep the wheels in ‘good condition’. This also means that wind boulders or similar rocks are avoided as much as possible.

right turn

All in all, it means that Curiosity is allowed to turn around again. Over the next few weeks, Curiosity will roll down and return to a place it’s been to before: a transition area between a clay-rich area and an area with large amounts of salt minerals called sulfates. The clay minerals formed when the mountain was wetter, speckled with streams and lakes. The salts may have formed when Mars’ climate dried up over time.

New route

In the meantime, a new route has already been mapped out. For the foreseeable future, Curiosity will continue to explore Mount Sharp — the three-mile mountain at the center of Gale Crater that the rover has been climbing since 2014. While exploring, Curiosity studies several sedimentary layers formed by water billions of years ago. These layers help scientists understand whether microscopic life ever existed on Mars.

Incidentally, after 10 years of intensive research on Mars, Curiosity is starting to rattle here and there. For example, certain braking mechanisms on the robot arm that carries that drill turn out to be worn out. However, Curiosity has spare parts that ensure that the arm can continue to operate. Engineers are now studying how to keep this essential robotic arm working for as long as possible.

Source material:

†NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover Reroutes Away From ‘Gator-Back’ Rocks” – NASA

Image at the top of this article: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS