It cautiously suggests that many other planets are also being treated at birth to the organic molecules that ultimately led to the emergence of life here on Earth.

Astronomers have delved into the protoplanetary disks of some very young stars in a new study. These are the flattened disks of dust and gas around a young star in which planets see the light of day. The researchers managed to map the chemicals in these ‘nursery rooms’ in unprecedented detail. And it turns out that planet-forming disks are teeming with organic molecules.

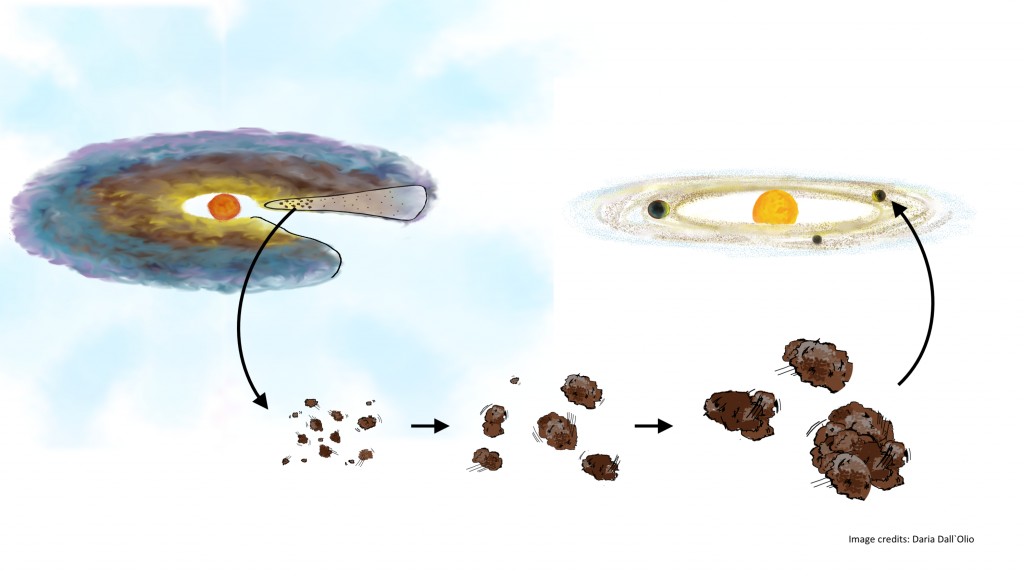

What we know so far is that most planets form when a molecular cloud collapses, creating a young star. The system starts spinning a little faster and a flattened disk forms around the young protostar; the protoplanetary disk. In the millions of years that follow, particles in the disk collide, causing these particles to clump together into increasingly larger objects. And that’s how planets are born (see also the image below).

Illustration of the first steps of the formation of planets. Top left: a protoplanetary disk consisting of gas and dust particles. Below: these particles clump together to form increasingly large agglomerates. Top right: This eventually leads to planets around a young star. Image: Daria Dall’Olio.

Scientists suspect that our young Earth was bombarded with building blocks for life through impacts from asteroids and comets. These would have formed in the protoplanetary disk around our sun. But scientists weren’t sure whether all protoplanetary disks contain complex organic molecules from which life can arise.

Study

To find out, researchers used the ALMA telescope to study five protoplanetary disks located between 300 and 500 light-years away from Earth. The researchers were specifically looking for three molecules, namely cyanoacetylene (HC3N), acetonitrile (CH3CN) and cyclopropenylidene (c-C3H2). Finally, after a two-year study, the researchers come up with a surprising discovery. “These planet-forming disks are teeming with organic molecules, some of which are involved in the origin of life here on Earth,” said researcher Karin Öberg.

The four protoplanetary disks studied and their properties. Image: Dr JDIlee/University of Leeds

The researchers found the molecules in four of the five discs observed. In addition, the molecules appear to be abundant; even to a greater extent than the team had anticipated.

Building blocks for life

This means that most of the protoplanetary disks studied contain a large number of building blocks for life. So perhaps the Earth is not as unique as we sometimes think. Because the study cautiously suggests that many other planets are also treated at birth to the organic molecules that ultimately led to the emergence of life here on Earth. The necessary fundamental chemical conditions may therefore occur on a much larger scale in the Milky Way. “This is really exciting,” says Öberg. “The chemicals in each disk will ultimately influence the type of planet that forms and determine whether or not the planets can harbor life.”

Place

The new maps also show that the chemicals are not uniformly distributed across each protoplanetary disk. Instead, each disk is a different planet-forming “soup”; a mishmash of molecules. This suggests that planets are born in different chemical environments. Each planet may be exposed to different molecules during its formation; depending on its precise location in a disk. “Our maps show that it matters a lot where in a disk a planet forms,” explains Öberg. “So two planets that form around the same star can have very different organic stocks.” It means that the chemistry found in a single disk is much more complicated than researchers thought. “Each single disk looks very different from the next,” said study researcher Charles Law. “The planets that form in these disks will experience very different chemical environments.”

Asteroids and Comets

Thanks to the ingenious ALMA telescope, researchers have been able to gain insight into the inner regions of protoplanetary disks and identify single molecules. Interestingly, the molecules are mainly located in areas where asteroids and comets are also formed. And that means that these celestial bodies may – just as happened on our Earth – provide the building blocks for life on other planets. “The main finding of this study is that the same ingredients that were necessary for life on Earth are also found around other stars,” said researcher Catherine Walsh. “It is quite possible that the molecules needed to initiate life on planets are already readily available in all planet-forming environments.”

One of the next questions the researchers hope to answer is whether there are even more complex molecules in the protoplanetary disks. In addition, they plan to study even more protoplanetary disks in the future. Because a larger sample size can further strengthen the conclusions drawn from the current study.

Source material:

“Planets form in organic soups with different ingredients– Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

“Astrophysicists identify large reservoirs of precursor molecules necessary for life in the birthplaces of planets” – University of Leeds

Image at the top of this article: WikiImages via Pixabay