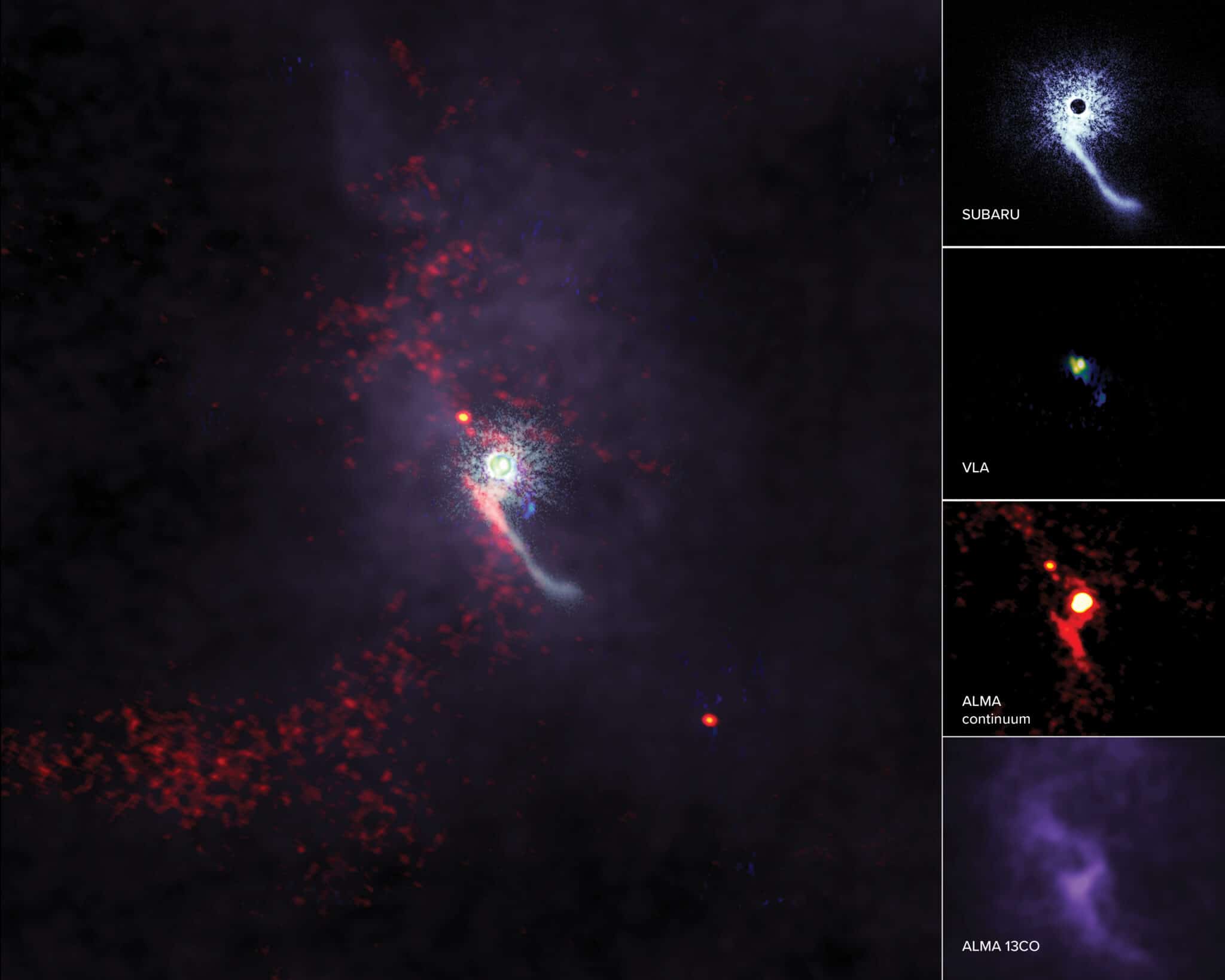

Using ALMA, researchers caught the “invader” red-handed, creating chaotic, sprawling streams of gas and dust in the flattened disk surrounding the young protostar.

Scientists have witnessed a rare occurrence in space. A lone star managed to penetrate the star system Z Canis Majoris and brutally disrupt the protoplanetary disk – the birthplace of planets. Although astronomers know that such events occur thanks to computer simulations, they have rarely been detected. “It’s equivalent to the probability of capturing lightning hitting a tree,” said researcher Ruobing Dong.

Z Canis Majoris

The intruder turns out not to be tied to his own system. As the star narrowly passed Z Canis Majoris, it then interacted with the environment around the binary protostar. This led to the formation of chaotic, sprawling streams of gas and dust in the oblate disk surrounding Z Canis Majoris.

This composite image includes data from the Subaru Telescope, Jansky Very Large Array, and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, revealing in detail the perturbations in the protoplanetary disk. Image: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), S. Dagnello (NRAO/AUI/NSF), NAOJ

As mentioned, it is a rare sighting. “Observational evidence of such flybys is hard to come by,” Dong said. “These events take place at lightning speed, making it difficult to capture on image.” Nevertheless, thanks to the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Very Large Array (VLA) the researchers succeeded in doing so. “This discovery shows that close encounters between young stars harboring disks are really happening,” Dong said. “It’s not just theoretical events in computer simulations.”

Intruder

The fact that it was an intruder that overturned the protoplanetary disk of the star system is quite special. Disruptions in such disks are usually not caused by intruders, but by brothers or sisters growing up together in space. “Stars usually grow up together,” said researcher Hau-Yu Baobab Liu. “The twins, or even triplets or quadruplets that are born together, can be pulled towards each other by the mutual gravitational pull and thus come close to each other. Then some material can be ‘stolen’ from protoplanetary disks, which then form extensive gas streams. From this, astronomers can conclude that the star has encountered other stars.”

Structure

In the case of Z Canis Majoris, the morphology and structure of the gas flows reveal that this is not a relative, but an intruder. “When a stellar encounter occurs, it causes changes in disk morphology,” explains researcher Nicolás Cuello. “Think of spirals, curves and shadows. You can actually see them as fingerprints. By looking very closely at Z Canis Majoris’ disc, we managed to reveal several fingerprints from the flyby.”

Future

The question now is how the intruder’s visit will affect the protoplanetary disk of Z Canis Majoris and the planets that may be born in the system in the future. The answer to that question is yet to come, although it is quite possible that the event will affect the development of baby planets. “What we now know from this new research is that such flybys occur naturally and have a major impact on the gaseous disks in which planets are born,” Cuello sums up. “As the long gas flows around Z Canis Majoris betray, protoplanetary disks can be quite disrupted by such flybys.” Subsequently, this can also affect the star that houses the protoplanetary disk. “It can lead to violent outbursts,” Liu says. “It may also have unforeseen consequences for the development of the star system.”

The implications of this study extend beyond simply expanding our knowledge of the evolution and growth of young star systems. Scientists hope that by studying such events, they will also learn more about the origin of our own solar system. “Studying events like this gives us a glimpse into the past,” Dong says. “It may tell us more about what happened during the early development of our own solar system, the critical evidence of which is long gone. At present, ALMA and VLA have provided the first evidence to solve this mystery. The next generations of telescopes may open up windows we can only dream of right now.”

Source material:

“ALMA catches “intruder” redhanded in rarely detected stellar flyby event– National Radio Astronomy Observatory (via EurekAlert)

Image at the top of this article: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF)