If an error crept in while reading the calendar, it was automatically corrected on the shortest and longest day.

When you think of megalithic monuments, you immediately think of Stonehenge. The large, still mysterious monument consists of an earthen wall around a circular arrangement of large, primitively worked standing stones. For many years now, researchers have been trying to decipher what the famous building was for. The theory that Stonehenge was some kind of calendar seems the most convincing. But now researchers show that Stonehenge may not have been just any calendar, but “an autocorrect solar calendar.”

solar calendar

As mentioned, researchers have long suspected that Stonehenge was used as a calendar. This seems plausible when you consider the position of the stones and their alignment with the solstices. However, scientists still puzzled over how exactly this would have worked. In a new study Archaeologist Timothy Darvill and his team reexamined the stone circle and the positioning of the various rings that make up the structure, and explored how they might relate to a solar calendar.

That’s how it worked

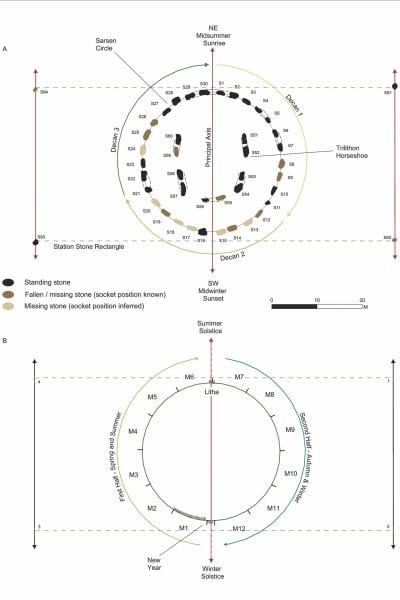

The researchers make an interesting discovery. Indeed, it seems very likely that Stonehenge served as a physical representation of the year, helping the residents of nearby Wiltshire keep track of the days, weeks and months. “The calendar is very simple,” says Darvill. “Each of the 30 stones in the sarsen circle (see box, ed.) represents a day within a month, which in turn is divided into three weeks of ten days each. The signature stones in the circle then mark the beginning of each week.”

Sarsen stones are the large stones that make up Stonehenge’s two iconic stone circles: the outer circle (consisting of vertically erected stones) and the inner circle (which also consists of vertically erected stones, each with a horizontal large stone on top). Recent research has shown that 50 of the 52 sarsen stones, according to their composition, come from the same area and were subsequently arranged in the same formation. This suggests that they functioned as a whole.

But that’s not all Darvill confirms. According to him, Stonehenge is based on a tropical solar year of 365 and a quarter days.

Tropical solar year

However, in order to bring the calendar into line with a tropical solar year, a kind of ‘in-between month’ of five days and a leap day every four years is needed. “This in-between month was probably dedicated to the gods,” Darvill surmises. “It is represented by the five trilithons (a structure consisting of two large vertical stones supporting a third horizontal stone, ed.) arranged in the middle. The four stones outside the sarsen circle made it possible to keep track of when a leap day was needed.”

Stonehenge as a solar calendar. Image: Timothy Darvill. et. already.

Autocorrect

In this impressive way, the shortest and longest day of every year would be framed by the same pairs of stones. One of the trilithons is also framed by the winter solstice, suggesting it may be marking the start of the new year. Moreover, the ancient inhabitants had built a solar calendar with autocorrect in this way. If an error nevertheless crept in when reading the calendar, it was automatically corrected on the shortest and longest day.

Other cultures

If you think a calendar with weeks of ten days and extra months looks a bit strange, such calendars were used in many cultures in the past. “At the beginning of the Old Kingdom around 2600 BC, this way of counting was widespread,” Darvill says. This suggests that Stonehenge stems from the influences of one of these other cultures. Darvill hopes to explore this further in the future. Ancient DNA and archaeological artifacts could reveal links between these cultures.

For now, the new study offers a whole new perspective on Stonehenge. “It shows that the monument was a place for the living,” Darvill says. “A place where the timing of ceremonies and celebrations was connected with the universe and the movement of the sky.”

Source material:

†Stonehenge served as an ancient solar calendar, new study suggests†

Image at the top of this article: Samuel Wölfl via Pexels