Last year, Suzuki unveiled its hydrogen-powered Burgman prototype, developed as part of the company’s efforts with the HySE consortium to make hydrogen a viable power source for internal combustion motorcycles and scooters. Now, a recently published patent application has revealed a new variation on that design that solves one of the prototype’s biggest problems: its size.

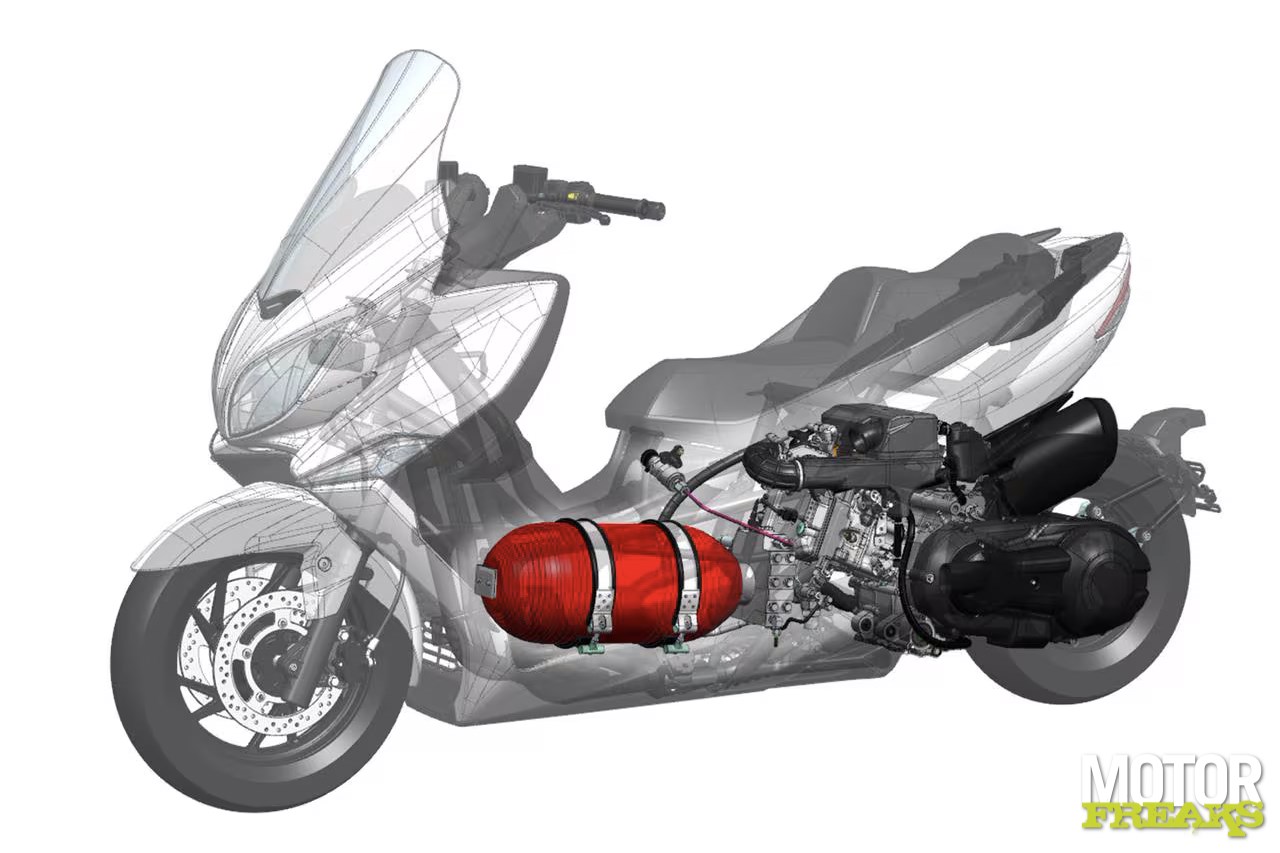

The original prototype for Suzuki’s Burgman ICE hydrogen-powered scooter, unveiled at last year’s Tokyo Motor Show – not to be confused with several generations of hydrogen fuel cell electric scooters Suzuki has made over the past decade, including a Burgman tested for 18 months by London’s Metropolitan Police – had an unusually long wheelbase due to the fuel system.

In order to fit the large hydrogen cylinder low in the bike’s chassis for an engine and transmission based on standard Burgman 400 components, the wheelbase of the first prototype was extended by a whopping 200mm by moving the entire drivetrain and swingarm rearward. That’s what this new patent attempts to prevent, while still allowing it to carry a significant amount of fuel.

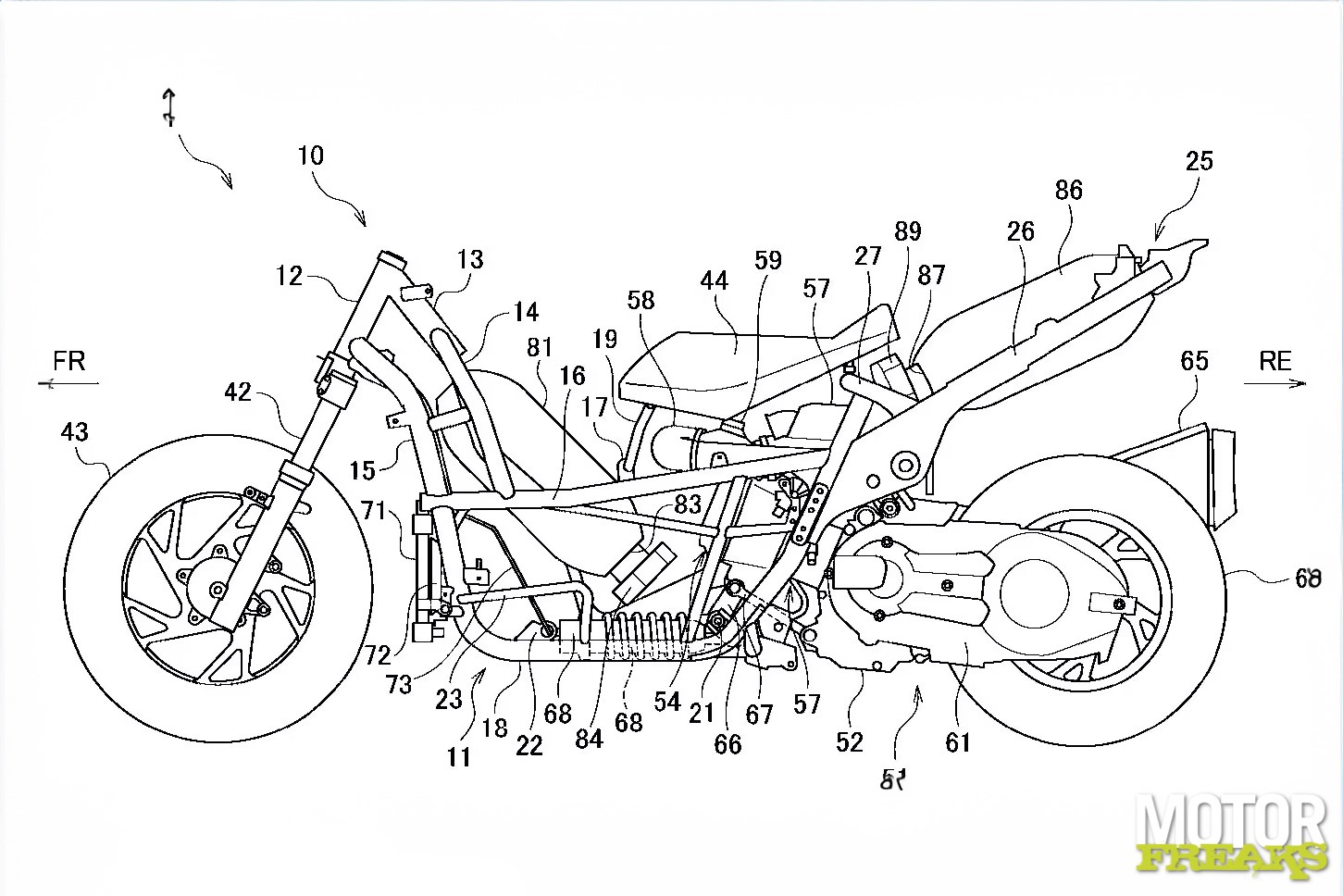

The solution is simple. Instead of a single, large hydrogen cylinder, the new design has two smaller ones. The first sits in front of the engine, as in the original prototype, but to save more space, it is tilted up at the front, so that the wheelbase of last year’s bike doesn’t have to be stretched.

the first prototype had a tank, and therefore a long wheelbase

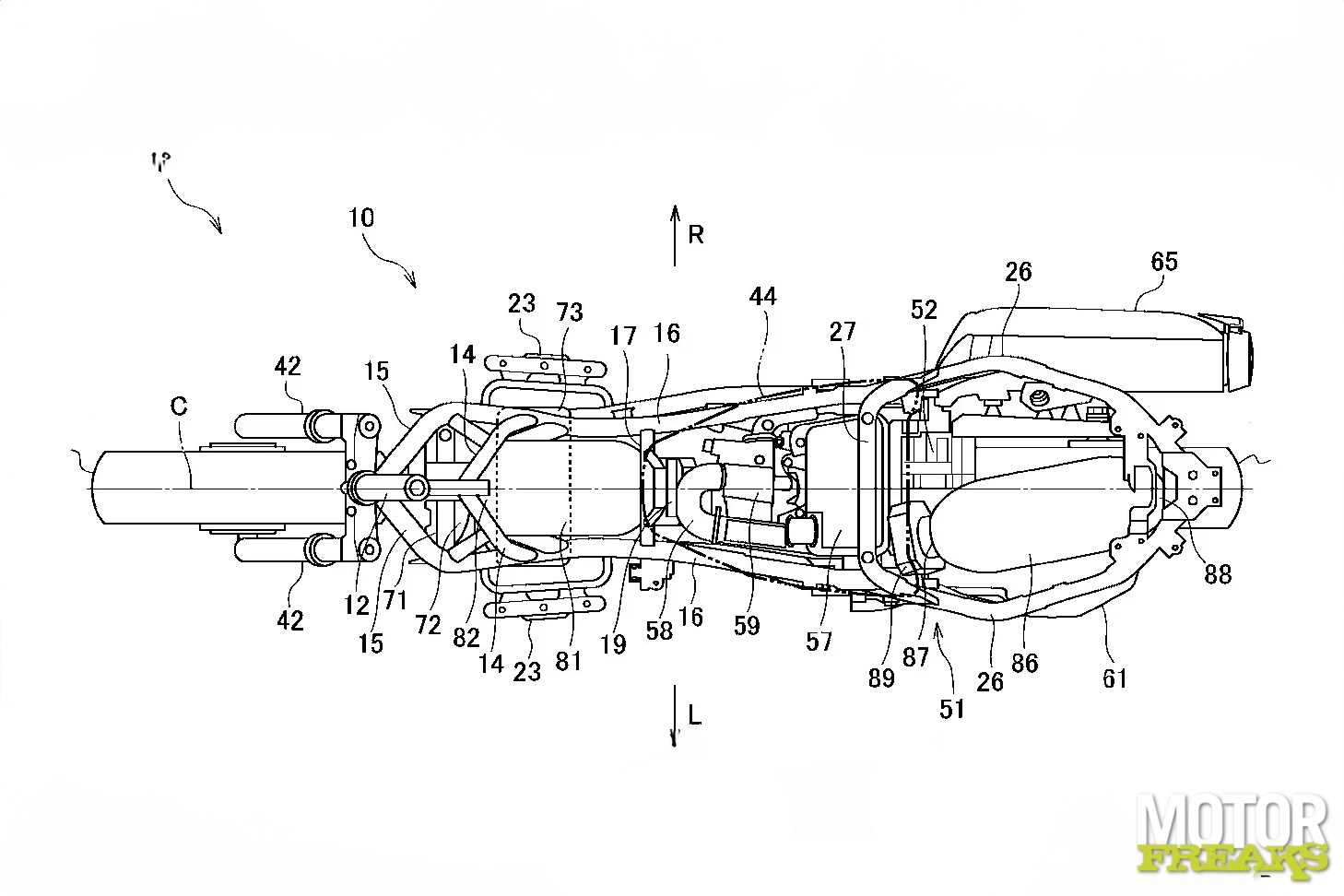

This allows it to fit into a standard, unmodified Burgman 400 chassis, without having to move the engine, transmission and swingarm rearwards. A second hydrogen cylinder is mounted at the rear, under the rear of the seat. When viewed from the side, it is angled upwards at the same angle as the seat, but when viewed from above, it is angled to one side, with the front of the cylinder towards the left side of the bike, to maximise the available space.

These solutions illustrate one of the key problems with hydrogen as a fuel. Not only is it much less dense than liquid hydrocarbons like gasoline in terms of volume, so you get less energy in the same amount of space even when the hydrogen is compressed, but the enormous pressure at which it is stored means that the tanks have to have very specific shapes to contain that pressure.

The new prototype has two tanks

While a fuel tank can be made of lightweight plastic, steel or aluminium and in any shape necessary to maximise volume within the confines of the motorcycle, hydrogen must be stored in cylinders capable of withstanding the 700 bar pressure to which the gas inside is compressed.

There are other considerations, too. For example, the radiator at the front of the engine must be isolated from the hydrogen tank at the front, with a deflector behind it to direct hot air downward rather than letting it raise the temperature of the hydrogen. And of course, the engine is heavily modified to run on hydrogen, with direct fuel injection to deliver the hydrogen to the combustion chamber after the intake valves close.

The problem of hydrogen storage remains a tricky one, as illustrated by Kawasaki’s supercharged hydrogen-powered prototype that made its first public demonstration run at Suzuka last month. However, the HySE consortium, which includes Japan’s Big Four motorcycle manufacturers and Toyota, is working on the problem of fuel systems and refueling, as well as making viable hydrogen combustion engines, so better solutions may yet be found.

– Thanks for information from Motorfreaks.