Astronomers have been eagerly awaiting it; the new data set from the Gaia space telescope. It was released today. And it turns out that there are quite a few surprises in it.

One of the biggest surprises is that the dataset shows that the space telescope is capable of detecting starquakes. These are very small movements on the surface of the star that change the shape of such a star. The telescope is not built to detect such quakes, but it can. In fact, according to the new dataset, the telescope has already seen thousands of stars tremble. And there are also stars whose theory dictates that they cannot tremble at all. Researchers are delighted with those spotted quakes — even if it means rethinking some of their ideas about how stars work and fit together. “Starquakes teach us a lot about stars, especially about their internal processes,” said researcher Conny Aerts. “Gaia opens a gold mine for the ‘asteroseismology’ of massive stars.”

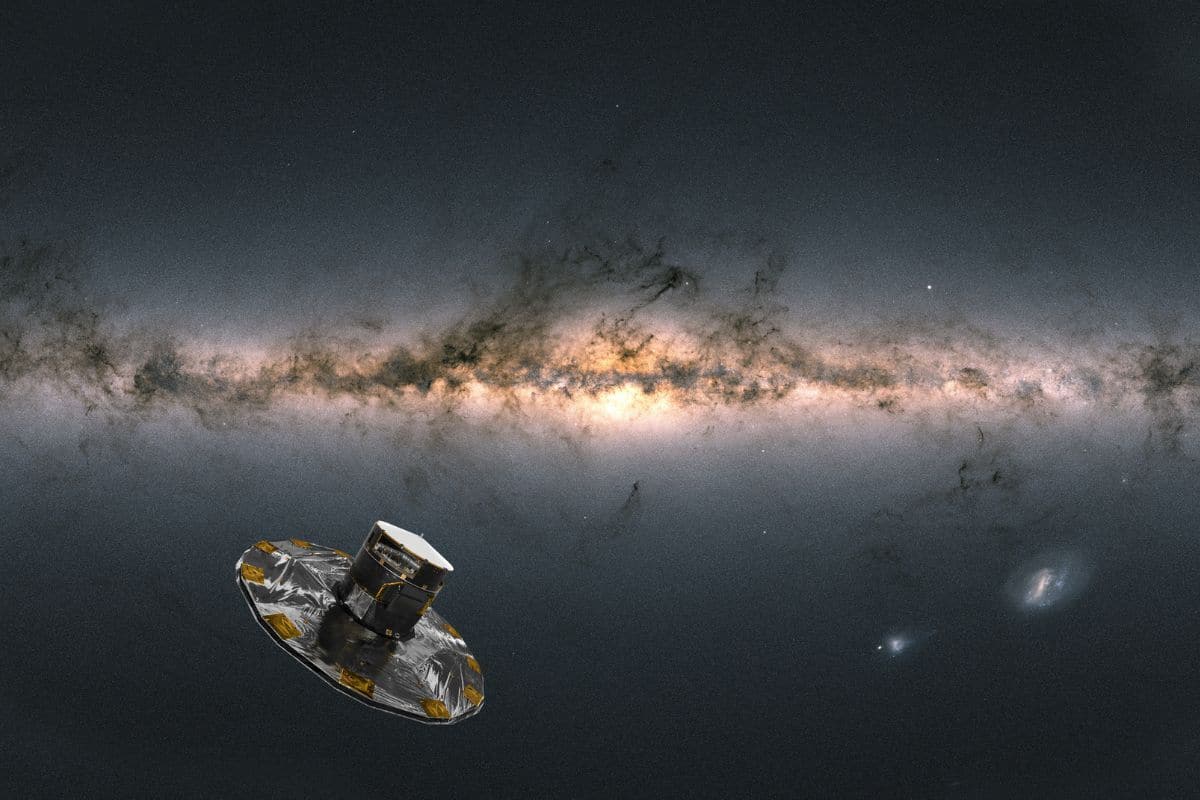

Gaia is a space telescope launched in 2013 by the European Space Agency (ESA) designed to survey approximately one percent of the 100 billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy. The main goal is to repeatedly determine for each of those 1 billion stars how bright they are, where they are located, how they move through the Milky Way, how old they are and how they fit together. It should result in the most accurate and complete multidimensional map of the Milky Way and provide more insight into how our galaxy has evolved over the past billions of years. By studying stars repeatedly and in detail, Gaia can also learn more about their surroundings. For example, small wobbly movements of stars can indicate that they are joined by another star or planet. Previously, researchers estimated that Gaia could discover between 10,000 and 50,000 exoplanets in this way. Similarly, the telescope could also detect brown dwarfs (failed stars) orbiting stars. In addition, thanks to the fact that it is also extremely sensitive to detecting faint and moving objects, Gaia lends itself very well to detecting dwarf planets and asteroids in our own solar system.

primordial stars

In addition to the starquakes, with the new dataset, Gaia also reveals the largest chemical map of the galaxy linked to 3D motion. In other words, we now know not only how many of the stars in our galaxy move through the galaxy, but also how they fit together. And that chemical makeup reveals more about the origin of those stars. For example, some stars in our Milky Way appear to be made of primordial matter. These stars mainly consist of the light elements formed during the Big Bang (hydrogen and helium). Other stars, on the other hand, harbor more heavy metals and that betrays that they are much younger; heavy metals are formed in stars and are only released when those stars die. Stars that harbor heavy metals are therefore formed from interstellar gas and dust that has been enriched with heavy metals by those dying stars and are therefore automatically much younger than those primordial stars that were formed when there were no or hardly any heavy metals available. And so, thanks to Gaia, we now know that both types of stars—the primordial stars and the later generations of metal-rich stars—are represented in our galaxy. In addition, Gaia shows that the stars that are close to the center and flat of our Milky Way are richer in metals than stars at greater distances.

Evolution of our Milky Way

In addition, Gaia – again based on the chemical composition of stars – has also determined that some stars we now find in our Milky Way don’t really belong here. They come from other galaxies. “Our galaxy is a beautiful melting pot of stars,” concluded researcher Alejandra Recio-Blanco. For astronomers, this diversity of stars is extremely informative. Because the chemical composition of stars reveals where they were formed. And if you combine that with the current position of stars, you can start to form a picture of the journey these stars have made and therefore also of the evolution of our Milky Way. “It shows the migration processes within our galaxy and the attraction from external galaxies,” said Recio-Blanco. “It also clearly shows that our sun, and we, are all part of an ever-changing system, formed by the merging of stars and gas of different origins.”

Binary stars, macromolecules and asteroids

In the dataset we also find information about the mass and evolution of more than 800,000 binary systems, or double stars. But the dataset also contains information about 10 million variable stars and still rather mysterious macromolecules between stars. And meanwhile, with new data on 156,000 asteroids, Gaia also sheds new light on the origin of our own solar system. “Unlike other missions that target specific objects, Gaia is a survey mission,” explains Timo Prusti, on behalf of ESA. “That means that as Gaia scans the entire sky with billions of stars several times, she will inevitably make discoveries that other more specific missions would miss.” And that is once again apparent from the rich data set that astronomers have had at their disposal since today.

It is not the first time that Gaia has disclosed a rich dataset; the telescope has been active for many years and has already released data twice before. The first time that happened was in 2016. Then the dataset revealed the position of 1.1 billion stars and the motion of 2 million stars. A second, much more extensive, dataset was unveiled in April 2018. And today, for the third time, a huge collection of data has been released. The dataset contains new and improved information about nearly 2 billion stars in the Milky Way. Thanks to the new data set, we now know how many more stars are chemically put together, what their color, mass and age are and what radial speed they have (i.e. at what speed they move towards or away from us). . But just like in previous years, releasing the data is only the prelude to more; it is now up to astronomers to take a closer look at the data and to interpret it. Prusti: “We can’t wait for the astronomical community to dive into our new data and learn even more about our galaxy and its environment than we could have imagined.”

Source material:

†Gaia Spots Strange Stars in Most Detailed Milky Way Survey Yet” – ESA

Image at the top of this article: ESA/ATG media lab (Gaia); ESA/Gaia/DPAC (Galaxy); CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Thanks to: A. Moitinho.