Its tongue was almost as long as its whole head: paleontologists have discovered the fossil of a Cretaceous bird that apparently could stick its tongue out, similar to today’s hummingbirds or woodpeckers. Which food he obtained in this way remains unclear, but it is possible that he licked nectar-like vegetable juices or licked at insects. The fossil, which is around 120 million years old, proves once again how highly developed some representatives of the extinct bird group of the enantiornithes already were, say the researchers.

The Cretaceous sky was not just the realm of the pterosaurs. In addition to these winged reptiles, representatives of the birds had already conquered the air: It is assumed that they developed from two-legged dinosaurs in the course of the Jurassic and Cretaceous Ages. Two lines emerged: the ancestors of our present-day birds and the so-called enantiornithes. They resembled modern birds, but had special wing characteristics and mostly snout-like beaks with little teeth. The enantiornithes were the dominant bird form in the Cretaceous period and already produced a considerable variety, as numerous fossil finds from all over the world attest. In contrast to the ancestors of our birds today, however, they all died out as a result of the asteroid impact 66 million years ago.

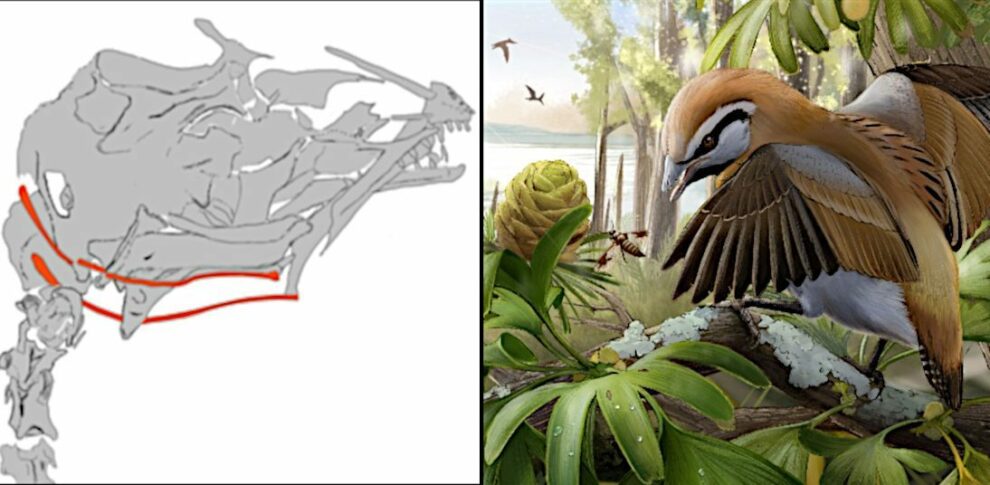

A Sino-American research team has now added an interesting new representative to this mysterious group of birds. The fossil, preserved in great detail, was discovered in 120 million year old sedimentary rocks in northeast China. It shows a bird from the group of enantiornithes about the size of a sparrow with unusual features. The paleontologists implemented it in the scientific name: The newly discovered species was called Brevirostruavis macrohyoideus – that means something like “bird with a short snout and a long tongue”.

A “cheeky” primeval bird is emerging

As the researchers report, the animal had a strikingly short, beak-like snout with small teeth, and an astonishing structure was also evident in the well-preserved skull: an extremely long hyoid apparatus. The bird therefore had long and curved bones that were connected to the tongue. All in all, it was almost as long as his whole head. As the scientists explain, birds don’t have large, muscular tongues like humans do. Instead, they have a series of rod-shaped elements made of bone and cartilage that make up the hyoid apparatus that sits at the base of their beak.

Many species of birds use their tongues in much the same way as we do – they carry food into their mouths, provide movement and help with swallowing. However, some of today’s birds such as hummingbirds and woodpeckers have taken the system to extremes: Their structures are about as long as or even longer than their skulls. This allows them to stick their tongues out wide to get to their food. According to the researchers, this suggests that Brevirostruavis macrohyoideus also possessed corresponding abilities.

Exactly why the bird from the Cretaceous period was able to snap out its mouthpiece far cannot be precisely clarified. Because no traces of the former stomach contents could be detected in the fossil. In principle, however, there are two possible options, say the paleontologists: the bird could have used its long tongue to prey on insects – possibly similar to woodpeckers, who use them to get insects out of holes in the wood. Perhaps the bird’s diet was similar to that of hummingbirds: it could have licked pollen or nectar-like liquids from plants.

Versatile Cretaceous birds

“We see a great variation in the size and shape of the skulls in the various representatives of the enantiornithes and that probably also reflects the great diversity in their food sources – or in which way they ate. With this fossil we can now see that not only the skulls but also the tongue structures could vary, ”says co-author Ming Wang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. His colleague Zhiheng Li adds: “Apparently these animals adapted to special foods by shortening their skulls and lengthening the tongue bones in the course of evolution.”

As the researchers finally emphasize, there was another interesting aspect of this development: the long, curved hyoid bone apparatus of the fossil bird consists of bones that are also found in the hyoid bone of today’s birds. But in Specht and Co, other bony structures shape the long tongues that were not found in the Enantiornithes. “Animals experiment evolutionarily with what they have available. This bird developed a long tongue using the bones it inherited from its dinosaur ancestors, and modern birds developed longer tongues using the bones that they specifically produced. This illustrates the flexibility in evolution: Birds use two different evolutionary paths to solve the same problem, namely to develop a long, literally protruding tongue, ”says co-author Thomas Stidham of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

Source: Chinese Academy of Sciences, specialist article: Journal of Anatomy, doi: 10.1111 / joa.13588