The telescope entered orbit around Lagrange point 2 last night.

And with that, a month-long and at times nerve-wracking journey has come to an end. L2 is the end point; from here on, James Webb will look for answers to countless pressing questions.

course correction

To enter orbit around L2, the James Webb telescope had to make one last course correction last night. The thrusters of the telescope were turned on for 297 seconds, or almost five minutes. This increased the telescope’s speed by about 1.6 meters per second, which was enough to get the telescope into the desired orbit. “Webb, welcome home,” NASA chief Bill Nelson said last night. “We are one step closer to revealing the mysteries of the universe.”

L2 or Lagrange point 2 is located about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. It’s a perfect spot for an infrared telescope like James Webb, because the sun, Earth, and moon are always on the same side of the telescope. That makes it pretty easy to keep the instruments that need to stay extremely cold away from these celestial bodies — and sources of heat. What also makes L2 a very attractive end point is that the telescope continuously maintains the same position in relation to the sun and the earth. This makes calibration and communication with the telescope easier. In addition, L2 is one of five Lagrange points around the Sun and Earth, where the gravitational pull of the two objects means that objects orbiting those Langrange points only occasionally need to activate their thrusters to maintain their location. And this saves a lot of fuel.

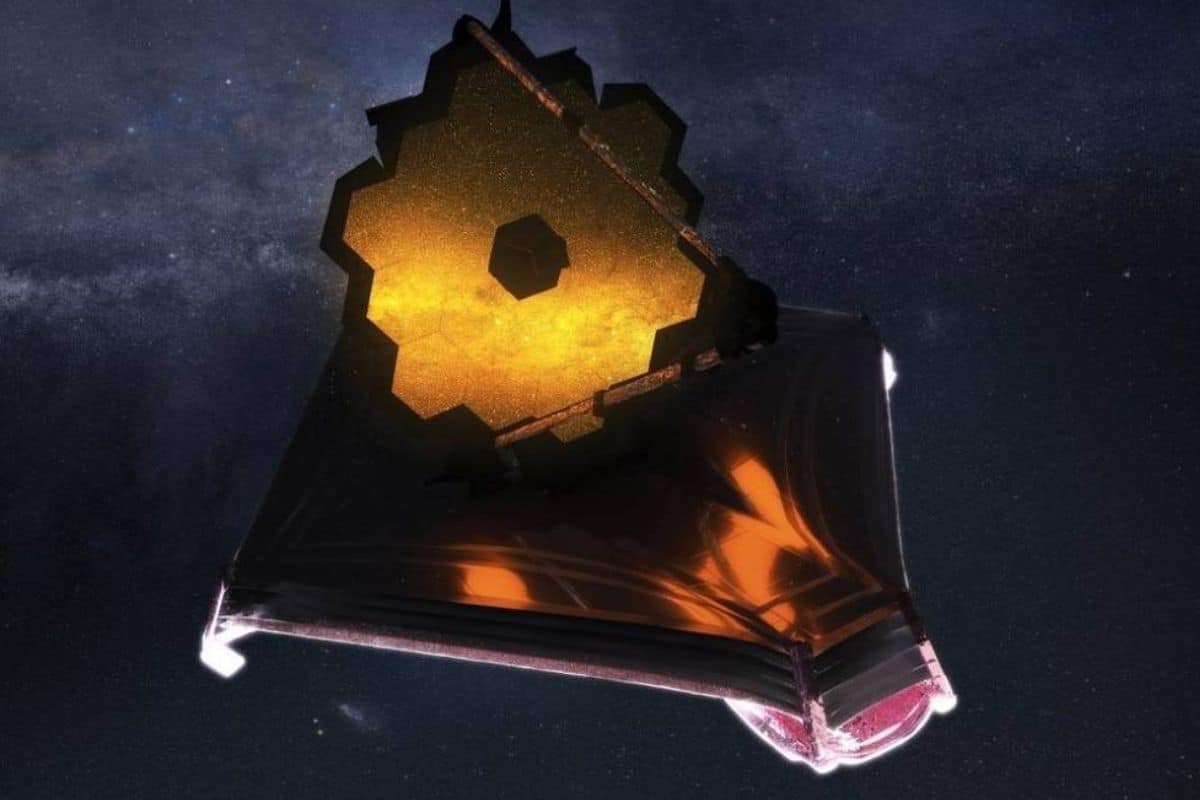

Image: NASA.

Although James Webb has now arrived at his final destination, the first images from the telescope are still some time away; scientists need another five months to prepare James Webb for observations. In the coming weeks, the focus will be on aligning the 18 segments that make up the main mirror. These must be aligned down to the nanometer, so that they can function together as one large mirror. In addition, James Webb also needs some time to cool down sufficiently and all scientific instruments still need to be calibrated. The first images are therefore not expected until this summer.

The mission

Astronomers are eagerly awaiting it. Because the expectation is that these images will change our view of the cosmos forever. For example, James Webb – the most powerful space telescope built to date – should be able to detect the first galaxies that formed shortly after the Big Bang and thus provide more insight into the evolution of the universe. In addition, the telescope will also investigate the formation of stars and planets, open the hunt for Earth-like planets and shed new light on the evolution of galaxies. In addition, the telescope will analyze the atmospheres of planets outside our solar system and thus provide more insight into the (perhaps biological) processes that take place on those planets.

Pending the first images, scientists can at least look back with satisfaction on the start of the mission, which at times was nerve-wracking. About the size of a tennis court, the James Webb telescope was ingeniously folded before launch and then unfolded step-by-step after launch. In addition, hundreds of moments could go so horribly wrong that the $10 billion telescope had to be considered lost. But so far the mission is running smoothly. In fact, thanks to the efficient launch and flawless journey to L2, James Webb is expected to last much longer than the expected 5 and hoped for 10 years; purely based on the amount of fuel left, the telescope could remain operational for at least 20 years.

Source material:

“Orbital Insertion Burn a Success, Webb Arrives at L2” – NASA

Image at the top of this article: Adriana Manrique Gutierrez, NASA Animator