ICE can continue until after 2035

It was close to being included in the historical canon in the EU by 2035. Thanks to e-fuels, this does not seem to happen. But what are they actually, e-fuels?

What is synthetic fuel?

You cannot make synthetic fuels with petroleum. You can also produce gasoline, diesel oil and kerosene from coal or biomass. In the past, this happened when, for example, oil was not or hardly available as a result of a war or political conflict. Nowadays we are also serious about synthetic fuels based on water plus CO2 from the air. Because an important part of the energy required for production is electricity, we often talk about e-fuels here.

Why e-fuels?

The exhaust of a combustion engine mainly produces water and CO2. The latter’s emissions in particular are increasingly undesirable, at least as long as the fuel is based on petroleum. However, no oil is used in the production of e-fuels, but CO2 from the air is used. The idea is that a combustion engine running on e-fuels emits almost as much CO2 as CO2 is required for the production of the same e-fuel. This should create a closed chain and the engine will therefore run CO2 neutral.

What are the advantages of e-fuels?

In various places around the world people can generate more electricity than they consume. Storing surplus electricity is usually difficult. You solve that problem by using that excess capacity for the production of e-fuels. Furthermore, no other infrastructure is needed, as is the case for hydrogen, CNG or electricity (in the Netherlands we have already come a long way with our charging infrastructure, but we are an exception in this regard).

E-fuels? We should all drive electric, right?

The coalition agreement of the Rutte III cabinet stated that only emission-free cars may be sold in the Netherlands from 2030. At that time (2017), the Netherlands was ahead of the European troops: the EU only decided to ban the combustion engine in 2022 and by 2035. At least, that was the initial plan. Last year it was decided in Brussels that the combustion engine would not be banned, as long as it runs on CO2-neutral fuel such as an e-fuel. Car manufacturers such as BMW therefore do not yet have an end date for the combustion engine.

Aren’t e-fuels coming too late?

A number of car manufacturers, including Volvo and Mercedes-Benz, have announced that they will stop producing cars with combustion engines around the end of this decade. Viewed in this way, the development of e-fuels seems to have come just too late. When we look at where these manufacturers sell their cars, we find that this is mainly in areas where there will be a comprehensive charging infrastructure for their EVs around that time, such as us in Western Europe. In regions where such a charging infrastructure is difficult to realize, residents are expected to be dependent on cars with a combustion engine for decades to come. When those engines run on e-fuels, we still comply with the climate treaties. In addition, we can keep the classic fleet running with e-fuels. So too late, no.

Is synthetic fuel also better for the environment?

No. As a result of the high temperatures in the combustion engine, oxygen from the sucked air still reacts with the nitrogen also present in that air, resulting in harmful NOx. This is also evident from tests on both the chassis dynamometer and on the road. In tests conducted on behalf of the European environmental organization Transport & Environment (T&E), the NOx emissions from e-fuels and fossil gasoline are virtually the same. Carbon monoxide (CO) emissions even appear to be slightly higher with e-fuels than with fossil gasoline. However, emissions of unburned hydrocarbons (HC) are up to 40 percent lower (but still not zero) and emissions of particulate matter (PM) decrease by almost 90 percent. Unlike fossil fuels, e-fuels do not contain sulfur. The current Euro 6 emission standards can easily be met, but measured at the exhaust, e-fuels are no better for the environment than fossil fuels.

How efficient is the production of e-fuels?

Just like green hydrogen, production requires electricity, and quite a bit of it. To put it into perspective, let’s look at a virtual fleet of x number of cars. If that x number consists of battery electric cars (BEVs) and you need one wind turbine to drive them, then for hydrogen production to drive the same number of fuel cell cars (FCEVs) the same distance you need three wind turbines and it is the same x number of cars running on e-fuels quickly requires the energy of five wind turbines to produce e-fuels. Now wind is free, but windmills are not. The same applies to hydroelectric power stations and solar panels. Regardless of the origin of the electricity, driving on e-fuels is therefore quite energy intensive. From an efficiency point of view, it is better to just drive battery-electric. On the other hand, a car with a combustion engine hardly contains raw materials such as lithium and other rare earth materials. So you are not dependent on dictatorial regimes that operate mines where people (sometimes even children) are exploited.

Where can I fill up with e-fuel?

Currently, only e-fuels are used in a few pilot projects; They are not yet available at publicly accessible gas stations around the corner. The current petrol and diesel oil that you fill up with is still petroleum-based and contains a small percentage of biocomponents. For example, Euro 95 E5 petrol contains a maximum of 5 percent bio-ethanol, E10 petrol contains a maximum of 10 percent bio-ethanol and B7 diesel contains 7 percent FAME (Fatty-Acid-Methyl-Ester, organic fat that has been esterified with an alcohol).

Can my car also run on e-fuel?

Yes, for the consumer, an e-fuel is indistinguishable from the regular fuel as we know it today. Your car does not have to be adapted or prepared for it, as is the case with E85, LPG or hydrogen, for example. This also makes e-fuels interesting for keeping the classic fleet running in the future.

What does it cost?

Currently, e-fuels are only produced on a small scale in pilot plants. As a result, the price of those currently experimental e-fuels is many times higher than what we now pay at the pump for regular fuels. Currently the cost price per liter is approximately €4.50. That is without distribution costs and, above all, without taxes. The cost price will drop quickly as scale increases. Will the price of e-fuels become competitive in the long term? That’s like looking at coffee grounds. In any case, you have to ask yourself what competitive is. No one knows what fuel prices will be in, say, ten years, let alone twenty years. If fossil fuels are still available at all. It is better to look at the price per kilometer at that time; then a comparison can at least be made with electricity and hydrogen.

How is e-fuel made?

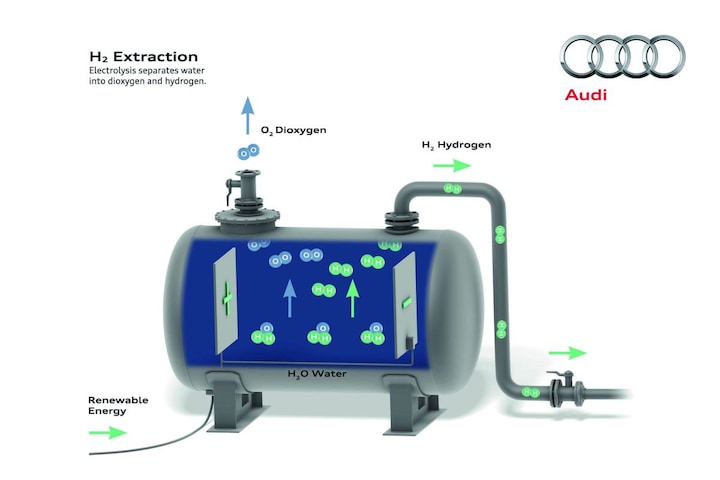

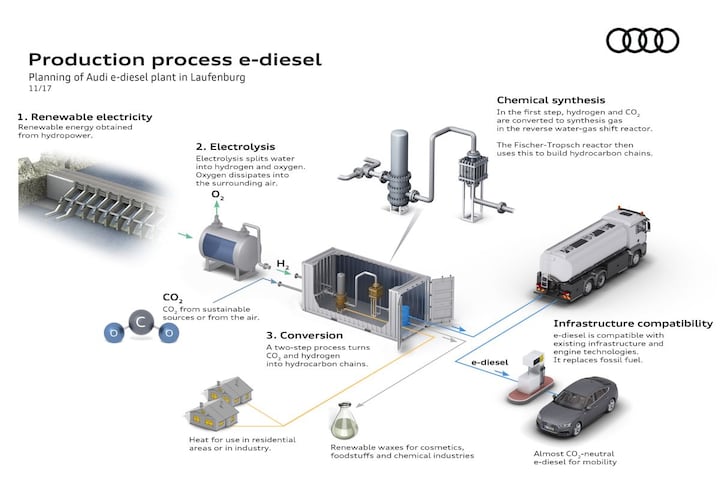

Simply put, the production chain looks like this: through electrolysis we split water (H2O) into oxygen (O2) and hydrogen (H2). We extract CO2 from the outside air in a parallel process. We then use the hydrogen and carbon (the C from the CO2) to create the desired hydrocarbon chains in a number of steps. With e-gas we are talking about CH4 (methane), with e-gasoline about C8H18 (iso-octane) and with e-diesel about even longer chains, such as C12H23.

If we zoom in a little more on the process, in the ideal green world we start generating electricity, hence the ‘e’ in e-fuels. We use this electricity to perform the electrolysis, just like the old oxyhydrogen experiment we know from high school. There is nothing fossil involved. Of course, you can also make hydrogen from natural gas, something that has been happening in the petrochemical industry since time immemorial. But that is gray hydrogen and it is now about green. To extract CO2 from the air, you can work with, for example, direct air capture (DAC). The CO2 is passed through a ceramic filter and bound to sodium hydroxide solution and then to slaked lime, after which calcium carbonate is formed. The CO2 is then released from the calcium carbonate. This is a fairly energy-intensive method, where green energy comes in handy. In the next phase, CO2 and H2 react to form methanol (CH3OH) and water. Finally, by passing the methanol through catalysts, it can be upgraded to, for example, e-gasoline. This upgrading of methanol can take place anywhere in the world. Methanol is easy to transport.

Who is pulling the cart?

For example Audi and Porsche. Audi has been committed to e-fuels for years. To boost its natural gas-fired A3 g-tron, Audi entered into an e-gas project in Werlte, Germany (just across the border from Emmen) more than ten years ago. The CO2 required for production comes from a nearby biomass power plant. It’s not Audi’s only experiment. From 2014 to 2016, Audi worked with Sunfire to produce e-diesel in a pilot project in Dresden and in 2017, Audi announced an e-diesel project in Laufenberg, Switzerland, together with Ineratec GmbH. Here electricity from a hydroelectric power station is used. Nowadays Ineratec also offers e-fuels for shipping and aviation. Together with the French Global Bioenergies, Audi announced a next project in 2018, this time to develop e-gasoline. After that initial announcement, we heard nothing more about this project.

Porsche’s plans seem more serious. Since 2020, the sports car manufacturer has been working with Siemens Energy in the Haru Oni project in southern Chile (which in local dialect means something like ‘land of the winds’). The parties here are not only working on perfecting e-gasoline production, but also on scaling it up. Furthermore, the choice of the production location took into account the relatively easy shipping of the e-fuel. Anyway, for now this project is still in its infancy.

What kind of numbers are we talking about?

The e-gas pilot plant in Werlte, Germany is good for 1,000 tons of CNG, just enough to allow 1,500 Audi A3 g-tron to drive 15,000 kilometers annually. The planned capacity of the Swiss e-diesel pilot plant is also quite modest: 400,000 liters of e-diesel per year (that’s less than fifteen tankers). Although this still compares quite favorably with the Porsche project in Chile: the Haru Oni pilot plant opened in December 2022 to produce 130,000 liters of e-gasoline in a year. However, after the start-up phase, this should increase to 55,000,000 liters per year in 2025 and even to 550,000,000 liters annually from 2027. This will require 660 wind turbines. Now 550 million liters sounds quite a lot, but it can only keep about 10 percent of Dutch petrol cars running. In 2022, we will all refuel 5,237 million liters of petrol in the Netherlands (and 5,215 million liters of diesel and 215 million liters of LPG). But hey, that’s the Netherlands. Global oil production in 2023 was 101.7 million barrels per day, or just over 16.2 billion liters per day, equivalent to 5,902 billion liters per year. Oil is not only used as a fuel – it is also a basic material in the chemical industry – but it does say something about the scale in which you have to think if e-fuels are to play a significant role at all. And to think that e-fuels require five times as much electricity as BEVs.

– Thanks for information from Autoweek.nl