It cautiously suggests that planets may see the light of day in far more places than was previously thought possible.

In our solar system, all planets orbit around one star. But such a lone star at the heart of a galaxy is certainly not the norm; astronomers suspect that at least half of all galaxies harbor two (or even more) stars that are in the grip of each other’s gravity. The big question is, of course, whether planets can also form in such systems.

Planets with two or three stars

We can now answer that question in the affirmative. Several planets have already been discovered that are part of a binary star system. Many planets with even three stars have already been found. Recently, for example, KOI-5Ab. The planet orbits a star that is part of a triple star system. But what researchers have never seen is a planet that actually orbits all three stars. Until now. Because researchers now think they are on the trail of such a planet (or even several planets). That can be read in the magazine Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

GW Orionis

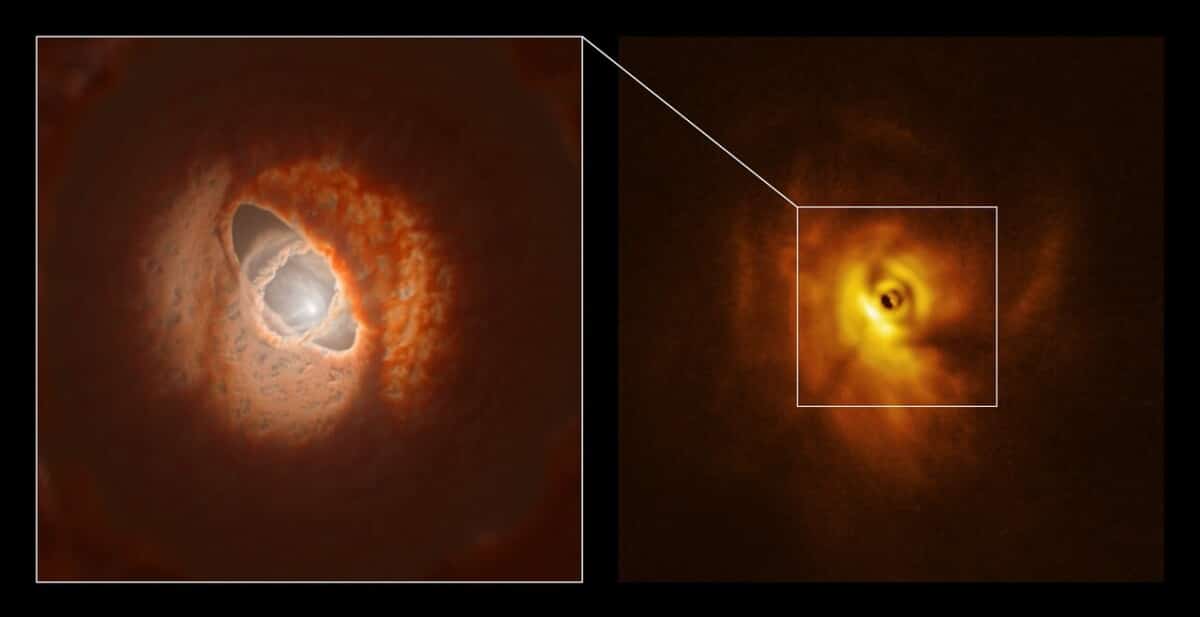

The research paper deals with a triple star system about 1,300 light-years away from Earth called GW Orionis. The star system already attracted the attention of researchers last year; then observations from the Very Large Telescope (VLT) revealed a protoplanetary disk that had been pulled apart around the three stars. Even then, astronomers had to conclude that it seemed very likely that planets could be found in that protoplanetary disk. But evidence for this was lacking.

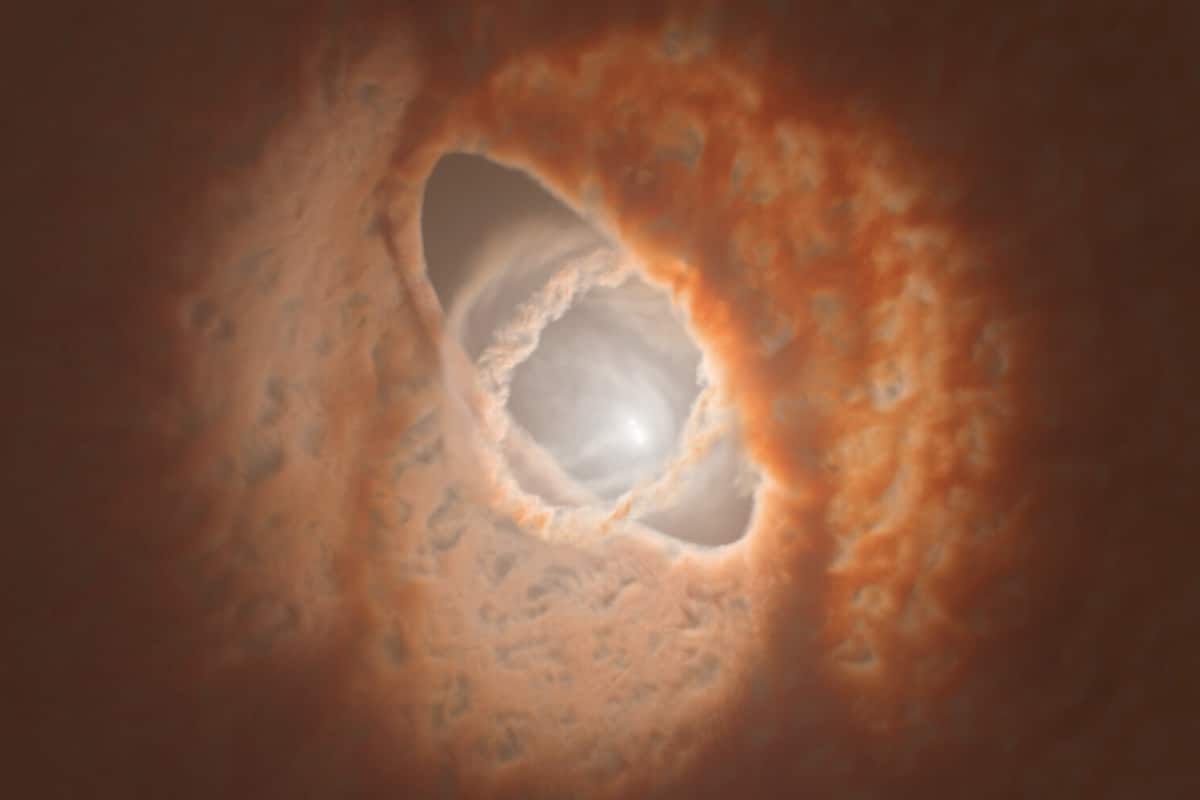

Here you can see the pulled apart planetary disk around the three stars. What immediately stands out, of course, is the inner ring. It is separate from the rest of the protoplanetary disk. Some researchers think that this can be explained by the formation of a planet in the disk. It has swept its orbit cleanly, leaving an annular void in the protoplanetary disk. Other researchers think they can explain the loose and tilted ring just fine in the absence of a planet and attribute it all to the competing gravitational pulls of the three stars. Image: ESO/L. Calçada, Exeter/Kraus et al.

ALMA

Using the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), researchers have now reconsidered this protoplanetary disk—particularly the annular void within it. And those new observations – in combination with simulations – seem to strongly indicate that there really is a planet orbiting the three stars. And it may even involve multiple planets!

Simulations

Using models, researchers simulated the formation of the strange protoplanetary disk, which they had previously accurately imaged with ALMA. In one simulation, they let the three stars do the work with their gravity. In the other simulation, they threw in a hypothetical planet. Then they looked at the scenario in which a ring arose like the ring that we actually find around the three stars. The research shows that the ‘hole’ in the protoplanetary disk can best be explained by the presence of one or even more massive planets. You have to think of Jupiter-like celestial bodies that usually appear first in protoplanetary systems (rocky planets such as Earth and Mars follow later).

Because no planet is visible in the images made by ALMA, it is not yet conclusive that a planet orbits around the three stars. But the system – again with ALMA – will be studied more closely in the coming months, which may provide the first direct evidence of the existence of a planet orbiting three stars. It would be very exciting, because it means that planets could form (and persist) in many more places than thought.

Source material:

“Research in Brief: UNLV Astronomers May Have Discovered First Planet to Orbit 3 Stars” – University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Image at the top of this article: ESO / L. Calçada, Exeter / Kraus et al.